As the Trump administration seeks to boost arms sales in Asia, the Shangri-La Dialogue is morphing into a marketing arm of Western arms exporters in Asia.

[timeless]

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc, Also read Lear Capital: Financial Products You Should Avoid?

At the Shangri-La Summit, U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis accused China of “intimidation and coercion” in the Indo-Pacific. “Make no mistake: America is in the Indo-Pacific to stay. This is our priority theater,” he said. What Mattis left unsaid was why America wants to stay in Asia and how U.S. defense contractors hope to turn the region into a weaponized cash cow.

What the Shangri-La Summit illustrated (and seeks to reverse) are the new economic and strategic realities in Asia, as reflected by vital, longstanding shifts in arms transfers in the region. While the U.S. defense system remains the most innovative in the world, U.S. global military leadership continues to erode. This is particularly clear in Asia where China increasingly accounts for investment and jobs in many economies (which tends to support regional stability), but the U.S. no longer doesn’t. Instead, and as a result, America’s role relies less on its now-waning economic dominance and increasingly on its military presence, which is legitimized on the basis of the alleged “Chinese threat” (which tends to destabilize regional stability).

Yet, new data indicates that even U.S. military position in the region is under relative erosion – as evidenced by the military transfers of China and Russia and some other countries in the region.

Arms exports pivoting to emerging Asia

In the past half a decade, the largest arms exporters have been the U.S., Russia, China and to a lesser degree France, Germany and the UK. Together, the six account for some 80% of the total volume of arms exports worldwide. Other exporters are minor players in the region, representing NATO (France, Spain, UK, Germany) and its partners (Ukraine, Israel, Sweden).

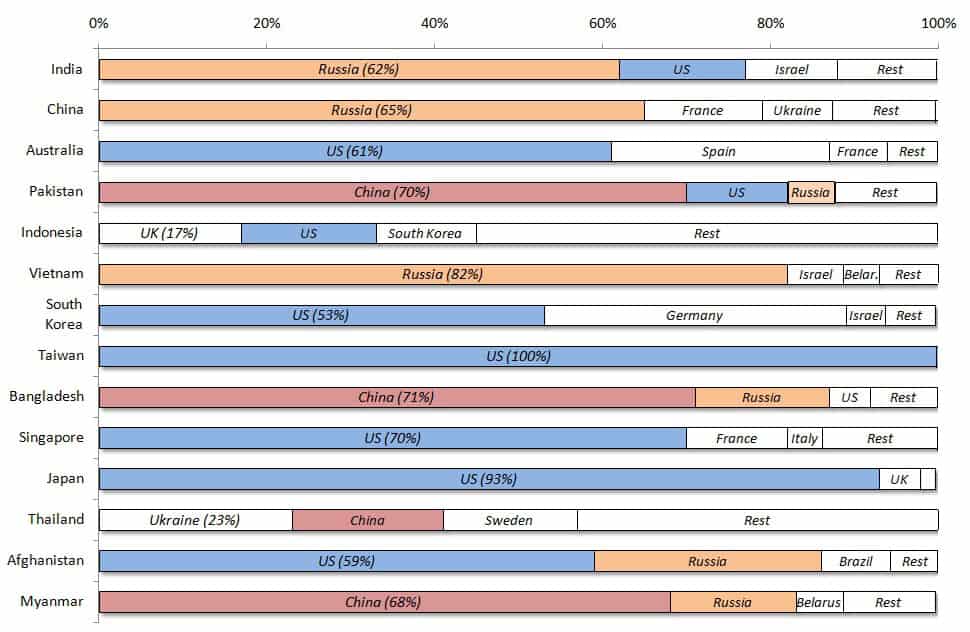

Today, the main recipient region of arms imports is Asia/Oceania, which accounts for some 42% of global imports – nearly as much as the Middle East and Europe together. In the postwar era, the U.S., along with a few NATO countries, was the primary arms supplier in Asia. Today, only two countries rely only on U.S. arms imports: Japan and Taiwan, which both source almost 100% of their arms imports from the U.S. Others tend to be more diversified, including Australia (61% from the U.S.) and South Korea (51%). Singapore (71%) has steadily increased its arms imports from the U.S., whereas Afghanistan (59%) is decreasing supplies from the U.S. (Figure).

The rising major arms exporters in the Asia/Oceania region include Russia and China. While China is becoming self-sufficient militarily, it still imports some arms, mainly from Russia. As an arms supplier itself, China is the primary supplier to Pakistan (70%), Bangladesh (71%), and Myanmar (68%), and a secondary importer to Thailand.

Interestingly, India, despite its rapidly-growing strategic reliance on the U.S., currently imports most of its arms from Russia (62%) and only 15% from the United States. Vietnam is a similar case. Despite its strategic reliance on the U.S. in the Southeast China Sea disputes, it depends almost exclusively on Russia (82%) for arms supplies. Furthermore, Russia remains a vital secondary arms importer to Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Myanmar.

Indonesia and Thailand hedge their bets more than their peers. The former relies on imports from Western powers (U.S., UK, South Korea), whereas Thailand’s importers are more diversified geographically (Ukraine, China, Sweden).

Figure: Top-14 Arms Importers in Asia and their main suppliers*

Source: Data from SIPRI, March 2018.

Six trends in regional arms imports

In the postwar era, the U.S. still dominated much of Asia both economically and strategically. As decolonization swept across former (particularly British and French) colonies, America purposefully exploited the vacuum. Most importantly, amid the Cold War, it created the security architecture in the region – including the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) which was signed in Manila, Philippines, in the mid-50s – whose stated role was to contain the Soviet Union and Communism. Hence, the U.S.-led wars from the Korean Peninsula in the early 1950s and the massacre of almost a million alleged Communists and Chinese in Indonesia in the mid-‘60s to the war in Vietnam and the associated destabilization in the former Indo-China in the ‘70s.

Until the late ‘70s, when the SEATO was dissolved, these moves supported reconstruction particularly in Japan and South Korea, while the concern for “Communist expansion” (read: Mao’s China) also translated to supported economic expansion in two former British colonies, Hong Kong and Singapore, which favored U.S. military presence and associated economic spillovers in the region. As these four Asian tigers – the “newly-industrialized countries” – got back on their feet, they began to offshore productive capacity elsewhere (and associated US strategic power) in emerging Southeast Asia. In the Middle East and South Asia, the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), created in 1955 and dissolved in 1979, played a similar strategic role.

However, today, the region looks very different. America’s economic role is gradually descending, and even its military position, as reflected by U.S. arms transfers, has declined from the Cold War era. At the same time, China has matured into a major economic contributor in the region, particularly as economic spillovers associated with One Road One Belt (OBOR) initiatives are spreading.

Second, Russia and China offer increasingly sophisticated military technologies, but for a lower price than the U.S. and its advanced allies. Third, the cost factor remains a key consideration to countries that have been close U.S. allies in the past (Indonesia, Thailand). Others have been alienated by U.S. unipolarity (Pakistan, Afghanistan).

Fourth, in the past half a decade, India has been the largest arms importer worldwide and accounts for 12 percent of the global total. During the period, its imports from the U.S. soared by more than 550%: that’s one reason why the U.S. Pacific Command was renamed the U.S. “Indo-Pacific” Command. Understandably, Washington would prefer to contain China’s rise by endangering Indian rather than U.S. lives, somewhat like Imperial Britain once relied on indirect rule in India to minimize British casualties. In New Delhi, increased U.S. arms imports reflect the Modi government’s effort to diversify imports sources, however. If anything, India seeks for greater strategic independence. In the short-term, the interests of these two great nations are converging; in the long-term, they may diverge.

Some countries, like Australia and South Korea, rely on U.S. arms imports, but have joined OBOR initiatives. Assuming positive OBOR spillovers, other economies (Indonesia, Thailand) that are similarly positioned may be expected to diversify away from Western imports in the future.

Following the money – From IISS Shangri-La to General Dynamics

Hosted by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), the Shangri-La Dialogue has intimate ties with the British government and Western security interests. The IISS’s major funders are the world’s leading military contractors (Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon, BAE Systems, ADS Group), oil giants (BP, Chevron, Shell, Statoil), and major government and private sector interests, as evidenced by the IISS own reports. The summit itself is sponsored largely by the IISS’s military donors, as evidenced by its website.

What unites the IISS’ U.S. donors is not so much a concern over China than a concern of being left out of the rearmament party. In fiscal 2017, the U.S. sold nearly $42 billion in weapons to foreign countries, but $8 billion (20% of the total) to the Indo-Pacific region, which remained behind the Middle East. Yet, in global arms transfers, the Asia Pacific is the most lucrative region (over 40% of world total). As U.S. defense contractors see it, they could and should double their revenues in the region.

Unsurprisingly, then, U.S. Secretary of Defense, James Mattis is pushing for U.S. arms deals worldwide, especially in Asia. After retirement from the Marine Corps, Mattis served in the Board of Directors of General Dynamics, a leading U.S. defense contractor with $31 billion in annual revenues. It is led by Phebe Novakovic, former official of the CIA and the Department of Defense. Last December, Novakovic said the Asia-Pacific is a growing market for U.S. defense contractors. “People spend money on defense when they’re worried, and many of our allies in Asia are justifiably worried,” she added. To win over “unsophisticated buying authorities” and discourage national efforts to build indigenous capabilities, she advocated “upgrades to their current platforms… to be able to communicate to fight together should the need arise.”

Now, the point here is not to argue— as one might on the basis of a blood-testing startup embroiled in scandal, or the so-called Theranos debacle, another board membership that Mattis had to resign — that there is collusion between the U.S. government, the Pentagon, leading defense contractors and U.S. “allies in Asia.” Rather, the risks are in the moral hazards inherent in the (far-too) intimate ties among these different players. It is precisely such risks that will always make destabilization preferable to defense contractors, which is then legitimized by the government leaders as a “moral imperative.”

What the Asia Pacific needs is peace, stability and economic development. Left unchecked, rearmament in the region will ensure the eclipse of the Asian Century – before it has started.

Dr. Dan Steinbock is an internationally recognized strategist of the multipolar world and the founder of Difference Group. He has served at the India, China and America Institute (US), the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see https://www.differencegroup.net/

The original version was released by China-US Focus on June 7, 2018.