Kerrisdale Capital is short shares of Aurora Innovation Inc (NASDAQ:AUR).

We are short shares of Aurora Innovation, an autonomous trucking company we expect will never become a viable commercial operation. Aurora projects a vision of an autonomous utopia in which driverless trucks haul trailers between customers, avoiding both the cost of a driver and Hours of Service (HOS) restrictions that limit driver hours. But for that to happen, Aurora’s Driver would have to master hundreds of thousands of suburban roads, and the current crop of AI-powered self-driving models, including Aurora’s, are incapable of that kind of scale. In the real world, the only autonomy Aurora might enable is a hub-and-spoke freight system in which the middle highway miles are driven autonomously while local drayage stays manned. But the logistical dynamics of that system will make autonomous trucking unambiguously inferior to direct manned trucking on the vast majority of routes. Worse yet, on the small fraction of routes for which autonomous trucking might be competitive, Aurora’s profit potential will be puny.

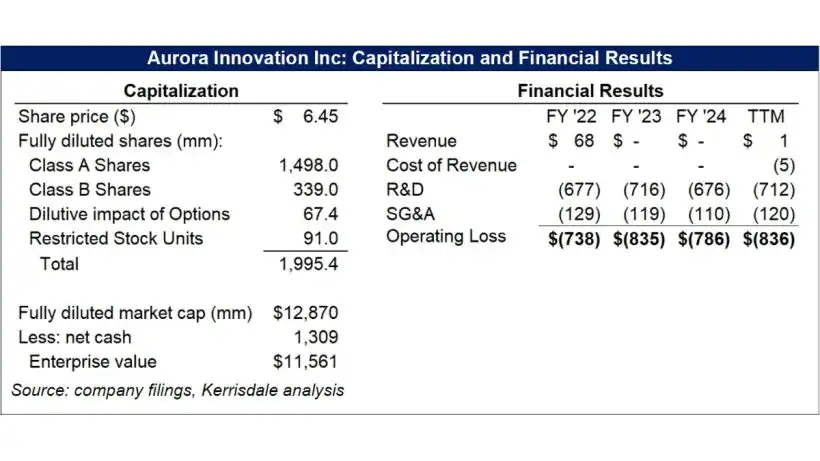

The problem for hub-and-spoke autonomy is that drayage – the first and last mile of freight delivery – is expensive and time-consuming. We demonstrate in detail how the cost and logistics of drayage will make autonomous trucking slower, more expensive, and less reliable than point-to-point manned trucking for any freight moving under 1500 miles. While that leaves very-long-haul shipping as a potentially viable market, the miles traveled in that space are a mere tenth of the 200 billion in Aurora’s asserted TAM. We also show how Aurora’s pricing on these routes will also come in far lower than the $0.65-0.85 per mile projected by management because drayage costs will consume a huge portion of the savings generated by removing the driver. The implied size of the entire market is just about $10 billion, smaller than Aurora’s market capitalization of $13 billion.

A hub-and-spoke freight system will also require…hubs. Someone has to incur the hefty real-world costs of building an autonomous trucking ecosystem. Even a foothold in the freight market would require massive amounts of hub investment. Aurora’s strategy for getting this done is to skip out on terminal construction and hope someone else steps up. Unsurprisingly, no one has. As for the actual trucks, while Aurora claims autonomous trucks will cost the same as comparable manned ones, executives at Aurora’s OEM partners told us they expect the trucks will be at least 50% more expensive. We also discovered a wide gulf between Aurora’s preferred business model and that of the trucking OEMs, who plan on capturing a much larger piece of the autonomous trucking economics than Aurora seems willing to give up.

In the end, the market for hub-and-spoke autonomous trucking is small, the required investment is huge, and the profit pool will have to be shared with truck and component manufacturers, competitors, and service providers such as terminal operators. The economics for Aurora are awful. Autonomous driving technology is best suited for the extreme density of economic opportunity in urban areas, and because highway trucking is the opposite, the resultant opportunity set is just impossibly difficult and too expensive to capture. Aurora investors should expect a decade of continuous dilution before arriving at a dead end.

I. Investment Highlights

Aurora promises investors a business model its technology cannot deliver. Its self-driving architecture has no chance of meaningfully navigating urban and suburban routes over the next decade, forcing the company to pursue a hub-and-spoke model in which driverless trucks travel between terminals immediately adjacent to highways, and last-mile manned shippers pick up and drop off shipments from and to individual customers. Unfortunately, these last-mile pickups and deliveries dramatically increase route costs and lengthen shipping times, rendering 90% of truck miles commercially uncompetitive for Aurora. The hub-and-spoke system would also require the construction and management of many dozens of expensive terminals, but because of the bleak return prospects, no one has stepped up to the task.

Even for theoretically viable very-long-haul routes, Aurora faces a host of other problems, including:

- Its progress piloting, testing, and actually deploying routes has been far too slow.

- The classic modular technology architecture underlying the Aurora Driver will probably be superseded by driverless players pursuing an alternative path more focused on end-to-end learning that’s cheaper and easier to scale.

- The actual trucks will still take a long time to hit the assembly line and they’ll be expensive premium vehicles once they’re finally commercialized, limiting their mass market potential.

- Aurora’s truck-OEM partners and terminal operators will ultimately garner much of the profit pool from autonomous trucking, in the far distant future when that profit pool finally materializes. This is somewhat analogous to how Tesla developed into a viable business not by just developing electric battery technology, but by building battery electric cars. Tesla is pursuing a similar strategy in autonomous driving, as is direct Aurora competitor Torc, which is owned by the largest truck manufacturer in North America, Daimler.

Aurora’s autonomous driver is unimpressive and difficult to scale, and Aurora is going to badly miss its own deployment projections. Waymo’s robotaxi is operational in 6 different regions covering 600 square miles and 15,000 miles of road in relatively difficult urban areas. At the same time, Aurora’s big accomplishment this year has been that its autonomous trucks have finally been deployed – apparently without the permission of its own OEM partner – and can cover a whole 200 miles of highway between Dallas and Houston.

Aurora has also spent 4 years testing and piloting its driver on the 600-mile trip between Fort Worth and El Paso. Despite claiming last year that training its driver for this trip merely “required bringing online only two new capabilities” relative to the Dallas-Houston lane, deployment still hasn’t occurred. And in October of last year, Aurora began testing for the 450-mile extension of this lane to Phoenix from El Paso and announced that it would be done later this year (2025). More than five years into the Aurora Driver’s development, it’s still taking a year to extend its capabilities a mere 450 “self-similar” highway miles. Notably, according to the Texas DOT, Aurora has shied away from testing and training on at least 5 other major highway lanes in the state, which is curious considering how straightforward management says highway scaling will be. Compared to the track record of Waymo’s much more complex and sizable expansion, it’s obvious that Aurora has been having a very difficult time scaling its autonomous model. There are 50,000 interstate highway miles across America and another 20,000 of state-level highways and freeways. If it’s going to take a year for every incremental 450 miles, driverless trucking is unlikely to make a dent across America anytime in our investing horizon. The company’s official guidance is that its autonomous trucks will cover 80% of the sunbelt in 2026 and more than two thirds of the entire country in 2028. Given the progress so far – or lack of it – we’d bet against that.

Direct shipping will be beyond the capabilities of the Aurora Driver, which – even if scalable – can only enable hub-to-hub shipping. The current generation of AI-based autonomous driving models, which are the basis for both Waymo’s and Aurora’s autonomous vehicles, can only enable autonomous driving within specifically defined parameters – commonly called the operational design domain (ODD). That’s because even though the elements of driving – perception, prediction, planning, and control – are governed by machine learning algorithms, the algorithms are themselves anchored by precise 3-dimensional high-definition maps, explicit definitions of environmental features (e.g., stop signs), and an overlay of explicitly defined rules. The difficulty of scaling self-driving mostly comes down to the painstaking engineering involved in extrapolating these model elements to new ODDs such as different weather conditions, lighting, geographic elements, or features of the road, and then maintaining them as changes accumulate over time.

In the case of Aurora, the geographic ODD is basically I-45 between Dallas and Houston. For Waymo, it’s the 6 precisely demarcated sections of the 5 different cities in which Waymos are available. When Waymo expands to new cities – like they’re doing with Miami and Washington DC at the moment – its aim is to expand its ODD to “rideshare destinations within this particular border,” and the distribution of those points is very dense, which makes expansion attractive to undertake and cost-effective to maintain. The problem for Aurora is that the distribution of points defined as “truck delivery destinations” – warehouses, distribution centers, etc – is highly dispersed. Even if Aurora were to get a handle on scaling highway travel across large swaths of the country, the problem of scaling beyond the highway to the final customer delivery points is – mathematically speaking – exponentially larger and would require mapping, engineering, and maintaining hundreds of thousands of miles of road, which is simply impossible in the context of currently operational self-driving methods.

Consequently, the only technically feasible business model the Aurora Driver can enable is a kind of hub-and-spoke freight ecosystem in which terminals are strategically placed in locations right off the highway around the country. Shippers would deliver their trailers to these terminals, Aurora-driven autonomous trucks would haul them on the highways between terminals, and customers will pick up the goods on the other end. The trouble with this is that it’s expensive, complex, and the market for it is just not very big.

Hub-and-spoke trucking isn’t usually faster or cheaper than direct human-driven freight, and it won’t be able to compete on most shipping lanes. The weak link in a hypothetical hub-and-spoke autonomous trucking system is the first and last mile, or drayage, which will still have to be transported the old-fashioned way: by manned truck. Drayage is time-consuming and expensive, which is widely understood in the intermodal shipping business. As we detail in this report, shipping to and from a terminal takes a few hours and requires building in time-buffers to meet terminal scheduling procedures. Those procedures, including delineating cutoff times and facilitating truck turnaround, also increase the duration of the trip. In addition, a supposedly key advantage of autonomous trucking – not being subject to human hours-of-service restrictions – will go to waste about half the time simply due to the business hours of drayage operators and shippers/customers, which don’t operate 24/7. We therefore expect that on trips under 1500 miles, autonomous trucking will provide no time-to-customer advantage over manned trucking. The multiple trailer-transfer points also add potential failure nodes in the process, reducing overall reliability.

Drayage also adds a significant cost to the shipping process, which we estimate – based on the disclosures of major first/last mile operators, publicly available price quotes, and conversations with logistics consultants – at about $1000 in total per trip, or about $500 each for the first and last mile. Aurora tries to fudge the significance of drayage costs by assuming a price tag of $100/side and relegating the assumption to the fine print in the footnotes of their investor presentations. But the reality is that drayage costs drastically reduce the driver savings that autonomous trucking is meant to enable. The cost of drayage, combined with the absence of improved service-times and increased logistical complexity, will mean that autonomous trucking will be structurally inferior to direct manned trucking on any routes under 1500 miles. It also puts a ceiling on the price that Aurora will be able to charge for the Aurora Driver at about $0.35-0.60/mile, depending on the distance covered in the trip, which is a lot lower than the $0.65-0.85 that Aurora has guided to.

Aurora’s TAM estimate is delusional. While Aurora often repeats that its TAM is the 200 billion miles driven by “combination trucks” – a statistic from the Federal Highway Administration – the Bureau of Transportation Statistics from which the FHA gets this data estimates that the total mileage of Class 8 trucks on trips over 500 miles is approximately 35 billion. This is critical because even Aurora admits that self-driving trucks aren’t much of an improvement over manned trucking on one-day trips, so it’s unclear why the company keeps repeating pollyannish TAM numbers when real statistics are readily available. We further estimate that fewer than half of those 35 billion miles are on trips over 1500 miles. In other words, the true TAM for autonomous trucking is about 17 billion miles – an order of magnitude lower than Aurora’s claims.

At the approximate $0.50/mile we believe is the maximum that Aurora would be able to charge for the software-based driver, that amounts to just about $8.5 billion for the entire market. Even if the number is slightly higher than that, there’s simply not a large enough market for autonomous trucking to justify either Aurora’s market capitalization of $13 billion or any major investment in autonomous trucking that’s going to rely on a hub-and-spoke structure. That may be at least part of the reason Waymo exited the business two years ago.

The autonomous trucks are going to cost a lot more than regular trucks, and require the construction of an extensive infrastructure to support their use. Besides a fairly limited market opportunity, Aurora has also misled investors about the increased cost structure of an autonomous truck ecosystem. Based on discussions with employees at Aurora’s own OEM partners – Volvo and PACCAR – the cost of the truck will be about 50% higher than the current average price of a Class 8 truck. The increased cost of redundant vehicle systems plus the autonomy-enabling sensor suite would consume as much as $0.15 / mile, based on our estimates, of the $0.50 / mile that Aurora could hope to charge for its service, further reducing the exploitable market size. We also found that Aurora’s partners have very different ideas about both when factory-scale autonomous truck production will begin and the right business model for the technology. Particularly significant is that Volvo’s idea of the autonomous trucking business is to sell an extremely premium product (the truck) with high levels of OEM service, which is impossible to reconcile with Aurora’s vision of saving its customers money on shipping costs and keeping some of those savings for itself.

Another aspect of costs that Aurora has simply shrugged off is the need for terminals in a hub-and-spoke system. Aurora has so far built two small terminals in Houston and Dallas, respectively, and set aside land for two more right outside Fort Worth and El Paso. But to come anywhere close to its own 2028 guidance, 40-80 terminals are needed, and the cost will run into the billions of dollars. At one point Aurora began recruiting a logistics team to undertake this build-out, but those executives are gone and Aurora confirmed last year that it’s not going to be responsible for building and maintaining the terminal infrastructure or the logistics planning.

We understand that in the quest to achieve the highest possible valuation, Aurora wants to just provide the software and let everyone else do the dirty work of actually building physical equipment and infrastructure. But inevitably, that’s going to mean that Aurora’s OEM partners and terminal operators are going to extract a chunk of the economics that Aurora will try to claim for itself. In the meantime, the dissonance between Aurora’s aggressive expansion forecasts and the almost complete lack of progress on the physical means to enable that expansion is palpable. We believe it signals a massive retrenchment to come in Aurora’s public guidance.

● ● ●

Aurora is stuck. The technology to enable true point-to-point autonomous freight simply doesn’t exist, and if it ever will, it’s going to be developed by one of Aurora’s growing set of competitors who are attacking the autonomous driving problem in a completely different (but as yet unsuccessful) way. For the time being, the best Aurora can do is enable a very kludgy hub-and-spoke freight system that has extremely limited appeal, with as yet no signs of anyone else taking up the mantle in helping to build it.