Miller Howard Investments commentary for the fourth quarter ended December 31, 2025, titled, "is there growth in your value?"

Let’s start with the part everyone already knows…

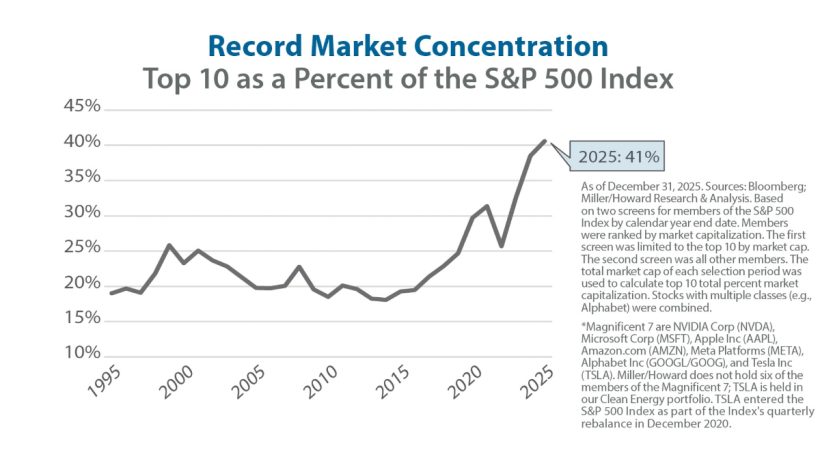

Over the last 10 years, equity markets have witnessed unprecedented outperformance from the companies with the largest market capitalizations. As the biggest companies grew, equity markets reached record levels of concentration with the weight of the top 10 holdings in the S&P 500 Index more than doubling to 41% (from ~19%), and surpassing the Tech Bubble high of ~26% in 1999. The “Magnificent Seven” (Mag 7)* have been the poster children for this dynamic. The Mag 7 accounted for an astounding 38% of the total return of the entire S&P 500 over the last 10 years and 44% over the last five years. Over 10 years, the Mag 7 went from just 11% to 34% of the S&P 500 Index.

What may be more surprising to investors is that style-based allocation alone does not eliminate this market concentration risk nor manage exposure to a narrow set of economic drivers. At the same time, index construction is creating fewer opportunities to diversify portfolios, further complicating matters for investors.

Imagine trimming exposure to Mag 7 holdings (or growth-style in general) and reallocating that capital into a value or income product—only to find some of that money going back into the very names you just trimmed. This dynamic is becoming increasingly common.

Are Indices Changing?

FTSE Russell periodically reconstitutes its indices. For the Russell 1000 Growth and Value indices, this includes reevaluating the companies in their indices to determine where they lie along the investment style spectrum. Russell uses three metrics (one value-, and two growth-oriented) to calculate a composite value score for each company that reflects how strongly the position displays value and growth characteristics. The constituents are ranked and an algorithm is applied to determine style index membership weights. Since a continuous style-scoring system is used (versus a binary system), holdings can be divided and allocated across both indices. In fact, over 250 holdings were held in both the Growth and Value indices earlier this year.

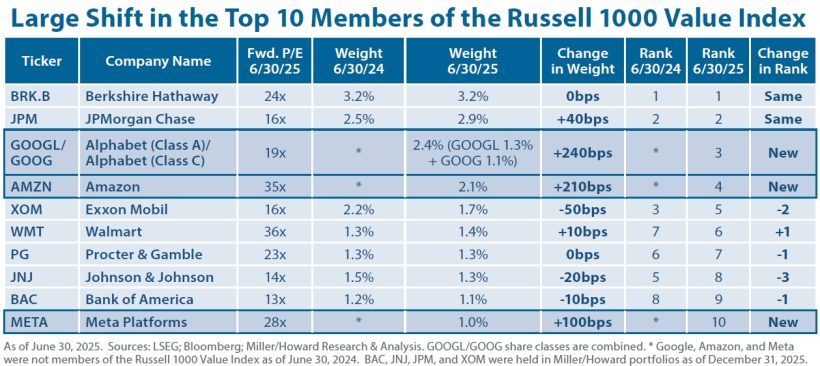

The 2025 reconstitution (on June 30) marked a key moment as three mega-cap stocks shifted from pure growth to part growth and part value due to lower growth scores and higher value scores: Alphabet (GOOGL/GOOG) shifted to 65% growth/35% value, Amazon (AMZN) shifted to 73% growth/27% value, and Meta Platforms (META) shifted to 82% growth/18% value.

This is not without precedent. In 2022, Google and Meta were categorized as partially value and were added to the value index at weights of ~1.65% and ~0.9%, respectively. However, during the 2025 reconstitution, Google, Amazon, and Meta all became top 10 positions in the Russell 1000 Value due to their outsized market capitalizations, despite only a portion of their total weight being allocated to value. The three positions represented a combined ~5.5% of the Value index. Perhaps even more counterintuitively, Google, Amazon, and Meta were top 10 holdings in both the Russell 1000 Growth and Russell 1000 Value indices at the reconstitution.

The Russell indices aren’t the only ones encountering these dynamics. S&P style indices are similar in many respects as they don’t force constituents to be 100% growth or value and allow weights to be split based on three growth factors and three value factors. The S&P 500 Index is divided roughly equally into growth and value indices with overlapping positions. S&P reconstitutes its style indices annually in December. At the end of 2024, the S&P 500 Value Index added some of the Mag 7 members with Apple (AAPL), Microsoft (MSFT), and Amazon making up the top three positions and comprising a stratospheric ~18% of the S&P 500 Value Index.

So, what’s the problem?

It’s a fair question. After all, index reconstitution is a mechanical process that is consistent and repeatable—core tenets of the passive process. It also seems fair to conclude that some companies don’t fit neatly into a style category.

If anything, the recent reconstitutions illuminate the fact that investing in passive indices requires an active decision. These indices, while not actively managing their holdings in a traditional sense, are making investment allocations based on their own key metrics. These criteria differ among providers based on what “value” or “growth” mean to the index provider. At the end of the day, we simply disagree with the output of this passive process.

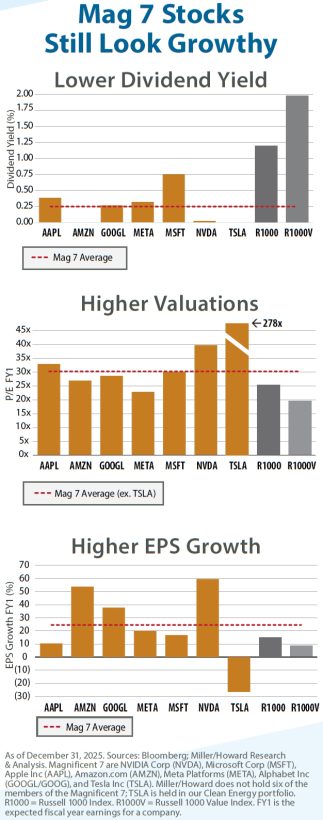

Historically, investors have generally agreed that, stylistically, value is predicated on identifying securities that are undervalued relative to their fundamentals and thus offer a margin of safety, while growth is predicated on identifying securities with above-average growth expectations and emphasizes upside potential. As a result, value stocks have typically exhibited higher dividend yields, lower valuation multiples, and lower growth rates than growth stocks.

While some of the Mag 7 may have, directionally, become more value-oriented based on year-toyear changes in key metrics, we think it requires some mental gymnastics to classify the Mag 7 as being true value names. At year end, on average, Mag 7 constituents had a lower dividend yield, higher price-to-forward-earnings (P/FE) ratio, and higher growth expectations than value names and the broad market in general. The dividend yield of Mag 7 constituents was ~100 basis points lower than the Russell 1000 and ~175 basis points lower than the Russell 1000 Value. The forward P/E of Mag 7 constituents [even excluding Tesla (TSLA) which was an outlier] was four turns higher than the Russell 1000 and nearly 10 turns higher than the Russell 1000 Value. Finally, the forward earnings-per-share (EPS) growth of the Mag 7 was nearly 10 percentage points higher than the Russell 1000 and nearly 16 percentage points higher than the Russell 1000 Value.

Why Should Active Investors Care?

It would be logical for a reader to be thinking, “But I’m an active investor, so this seems like a non-event.” The unfortunate reality is that index construction impacts active management decisions.

Active managers are under constant pressure to beat index performance (and/or provide superior risk-adjusted returns, income streams, etc.). For this reason, portfolio managers are, at the very least, aware of material changes to indices. But this awareness can also influence investment decisions. The inclusion of highflyers like the Mag 7 in value benchmarks clearly adds pressure to maintain performance. At the same time, value index inclusion provides cover to add names that may not have ordinarily been consistent with an investment approach. In aggregate, these dynamics affect portfolio composition and risk.

Looking Under the Hood

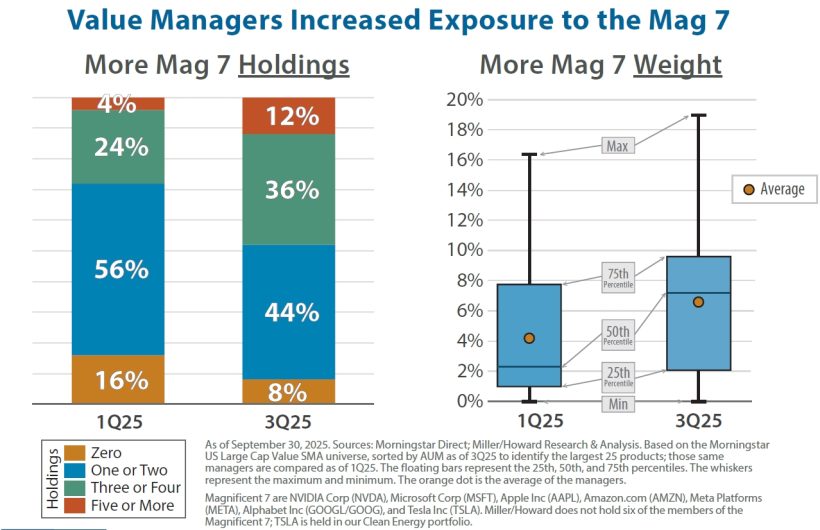

Are active managers providing style diversification? We evaluated the holdings of the 25 largest (by AUM) actively-managed large-cap value separately managed accounts as categorized by Morningstar. The exercise suggests that actively-managed value portfolios have materially increased investment in the Mag 7 over the last six months.

On March 31, 2025, (the quarter-end prior to the Russell reconstitution), 16% of portfolios held zero Mag 7 constituents and 72% held two or fewer. Six months later, by September 30 (one quarter post-Russell reconstitution), only 8% of portfolios held zero Mag 7 constituents and only 52% held two or fewer. In other words, nearly half of the value managers held three or more Mag 7 names. The number of portfolios holding five or more Mag 7 positions also rose to 12% (from 4%). The median portfolio allocation of US Large Cap Value SMAs to the Mag 7 increased from 2.3% to an astonishing 7.2%.

It was our initial assumption that value managers would have been more likely to add Mag 7 constituents than their income-focused peers. A cursory evaluation shows the facts proved otherwise. Within our analysis, over 25% of the products evaluated had “dividend” or “income” in the product name. These products had an above-average number and above-average weight in the Mag 7.

Our goal is not to disparage competing approaches. Yes, some value managers may have purchased these securities at levels that were consistent with their investment mandate. However, we have concerns that these names compromise style integrity. Ultimately, the high Mag 7 weight within value portfolios creates the illusion of diversification while heightening exposure to market concentration risks. We see this as a unique opportunity for investors to revisit overall portfolio diversification and to ensure each product is meeting its stated philosophy, investment universe, and portfolio objective.

Diversification with High Current Income & Growth of Income

Miller/Howard’s dividend focus is embedded in our corporate DNA and has remained unchanged for over three decades. Our disciplined approach maintains a close adherence to our investible universes across our portfolios, and we do not own the Magnificent 7 in our income-oriented portfolios. We believe this makes for differentiated portfolios that are consistent to their objective for high current income and growth of income compared to many other products in the market. While the investment landscape and products may continue to shift, we strive to continue to provide a truly diversifying income solution for investors.

Even putting concentration risk and potential style drift aside, we think the investment case is concerning.

It is admittedly easier to invest in what is working.

The problem is that it works until it doesn’t.

As we identified in our blog

Dividends: Valuations and Mathematics, published earlier this year, history suggests that 10-year returns skew negative when investments are made at elevated P/E multiples.

Read the full letter here.

Read more hedge fund letters here