Miller Howard's quarterly report for the second quarter ended June 30, 2025, is titled "Will Megacaps Outperform Forever?"

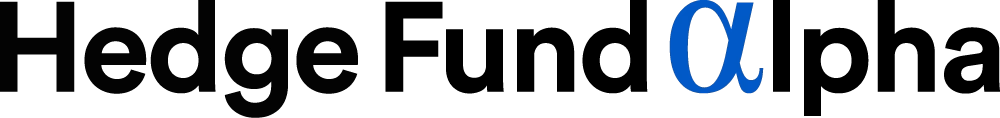

Over the past 10 years, investors have witnessed unprecedented outperformance from companies with the largest market capitalizations (“megacaps”). The biggest have become even bigger, while the vast majority of companies in the S&P 500 Index have underperformed. By weight, the top 10 megacap companies accounted for 18% of the S&P 500 at the end of 2014, growing to a record 39% at the end of last year. We have seen a slight easing of the trend this year, with the top 10 megacap companies representing 37% of the S&P 500 at the end of the second quarter of 2025. It’s unclear whether investors have finally cooled on the megacaps or if this is just a short-term reversal. We remain confident that market performance will eventually broaden, particularly given the extreme valuation spread—the trailing price/earnings (P/E) multiple for the top 10 market cap companies at the beginning of the year was 29.3x versus 24.4x for the S&P 500 as of quarter-end.

The performance skew towards the largest companies has made it difficult for the total returns of highyield dividend stocks to keep up with broad market averages. Over the past 75 years, high-yield dividend stocks have had an average annual return of 12.8% versus 11.5% for the S&P 500, but the story has been different over the past 10 years. Logically, it would be possible to find high-yield dividend stocks among the megacaps, but the reality is that recent P/E ratios are too lofty for almost all of the top 10 megacaps to pay a high, well-covered dividend. Looking at these companies at the end of 2024, none of them had a dividend yield above 1%.

Megacaps: Big Buybacks, Small Dividends

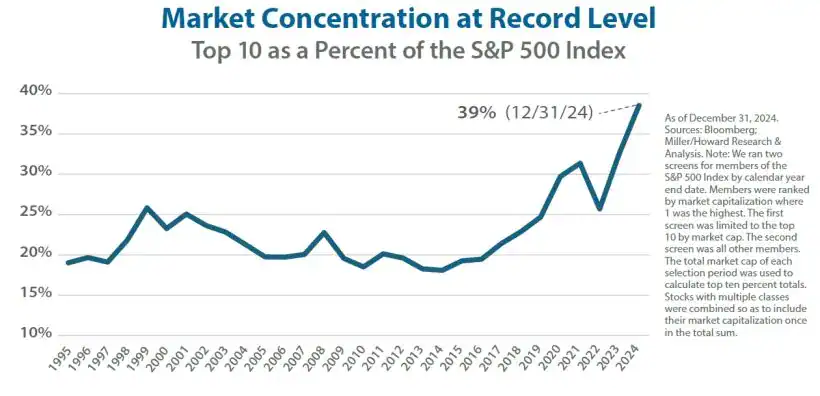

The outperformance of megacaps has been driven, at least in part, by their massive stock buybacks in recent years. Buybacks at the top 10 market cap companies used to be fairly close to dividends and in line with the overall market. Changes in corporate tax rates prompted an increase in buybacks for the overall market in 2018, but unlike the rest of the S&P 500, the megacaps have kept their foot on the buyback accelerator. As we have discussed in our past quarterly reports, both buybacks and dividends can help boost total equity returns. As investors ponder the uncertain environment, a key question is: What is more likely to grow going forward, dividends or buybacks? The ques- tion is critical because the market-leading megacaps are devoting big dollars to buybacks and relatively small sums to dividends.

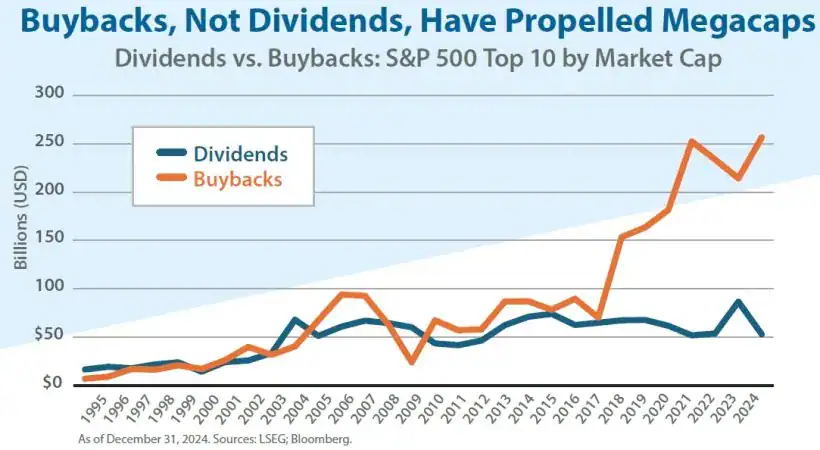

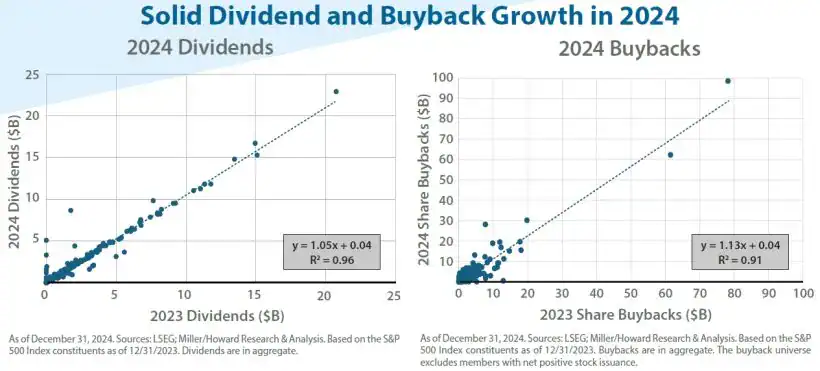

Every company has its own story, so we structured our analysis on a same-company basis, looking at the growth in dollars spent on dividends and buybacks for every company in the S&P 500 over the past 30 years (roughly 15,000 observations). Over these tumultuous 30 years, companies raised their dividends by over 2% on average. Perhaps more impressively, trailing dividends were highly predictive of the next year’s dividend with roughly 95% of the variance explained. In contrast, same-company buybacks dropped by 5% on average over the same period with much less of the variance explained. In other words, when con- sidering a stock investment, knowing the trailing dividends can be much more informative than know- ing the buyback history.

Dividend vs. Buyback Growth in Good Times and Bad

Pooling data across 30 years gives us a good estimate of the average same-company growth of dividends versus buybacks, but it masks just how different the growth rates can be in good versus bad years. Last year was a better-than-average year for both divi- dend and buyback growth. On average, companies raised the dollars devoted to dividends and buybacks by 5% and 13%, respectively.

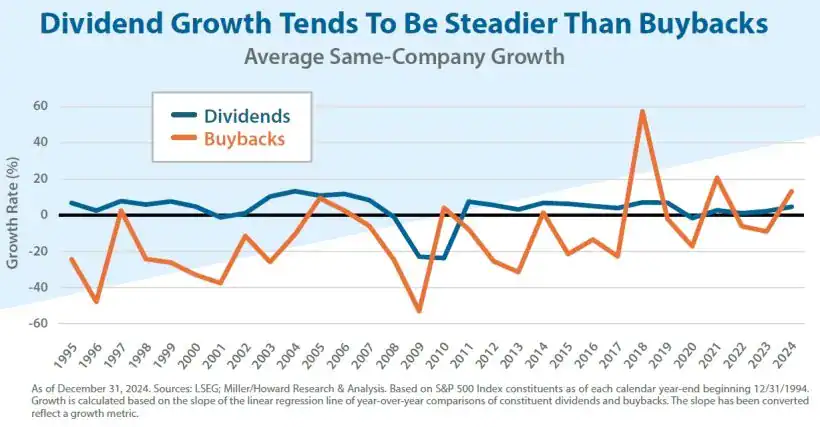

In contrast, same-company dividends fell by 23% in 2009. The chart shows that many companies raised their dividends in 2009, but there were some huge reductions that pulled average growth down. Same- company buybacks fell by 53% in 2009—evidence that management teams are more likely to cut buy- backs than dividends in challenging times.

Over the past 30 years, same-company growth rates for dividends have varied in a predictable manner, with growth going negative in 2001 following the Tech Bubble burst, in 2008-10 concurrent with the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), and in 2020 during the pandemic. For the other 25 years, same-company dividend growth was positive. Dividend growth fluctuated, but it was reasonably stable (other than during the GFC period).

In contrast, same-company buybacks not only shrank in most years, but they also gyrated tremendously. Some of the peaks and valleys are easily explainable, but many are head-scratchers. For example, same-company buybacks dropped by 31% in 2013, despite a growing economy and a booming stock market. In that same year, same-company dividends grew by 3%. Our overall conclusion is that buybacks are not terribly predictable.

At Miller/Howard, we have long argued that dividends are a clear signal that:

- The company is run for the benefit of shareholders. Public companies are run by executives who are strangers to the average investor and must earn investors’ trust. A dividend is a commitment by management to run the firm quarter-after-quarter with shareholder cash return as a priority.

- Management has confidence in the future profitability of their company. While management statements should be treated with appropriate skepticism, executives know more about their business than shareholders do. By committing to a regular dividend, management is using more than just words to signal that they expect their business to be resilient, even in a changing environment.

The outlook for the economy continues to be highly uncertain. Corporate earnings were ahead of expecta- tions in the first quarter of 2025, leading to a rebound in equity values. Yet tariffs remain both high and un- certain, and the full impact may not hit until the second half of 2025. Adding to uncertainty is the prospect for continued military conflict in the Middle East. In our view, this is not the time to chase expensive, megacap stocks, particularly given their reliance on buybacks.

Total returns for stocks can be decomposed into three parts: dividends, earnings growth, and price/earnings multiple expansion (see Miller/Howard’s 1Q 2021 Quarterly Report). The total returns, for high-yield dividend stocks, are skewed more towards dividend income than the broad market. Our view is that tilting towards dividends allows investors to benefit both from a lower-volatility source of returns as well as the strong tendency for dividends to rise over time.

Tough Environment for Stockpickers

Decades ago, an academic economist, Burton Malkiel, asserted that choosing stocks randomly had just as good of a chance of beating the broad market as professional stock-pickers. Portfolio managers with track records of beating benchmarks disagreed, but then came the real twist of the knife—in 2013, David Harding, a famous quant researcher, pointed out that stocks chosen at random had a better than 50/50 chance of beating the market. The reason given was that value stocks and small caps generally outper- form over time.

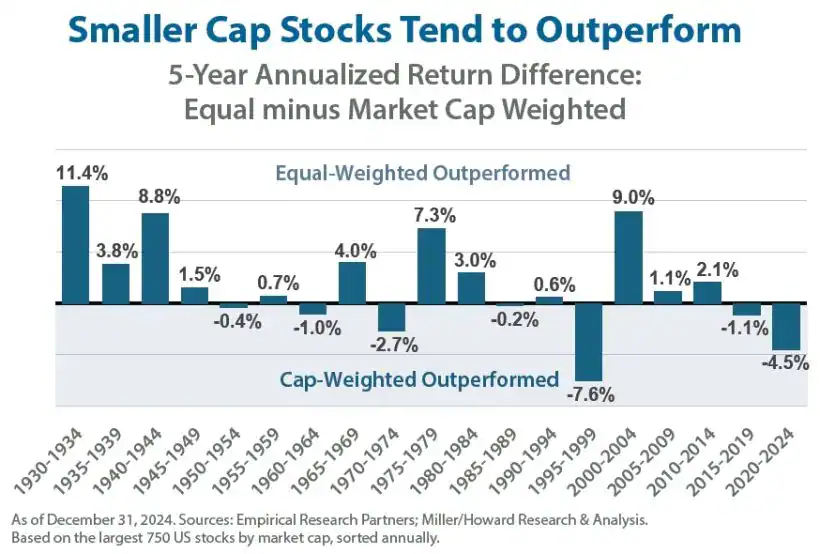

Anyone who began following the stock market in the last 10 years will find that statement puzzling given that large, expensive stocks have decisively outperformed the S&P 500 Index in the most recent decade. The easiest way to illustrate the disconnect between recent outperformance by larger cap stocks versus smaller cap is to compare returns of capitalization-weighted stocks with equal-weighted stocks—same stocks, differ- ent weights. When performance tilts towards the larger caps, the cap-weighted index outperforms, as it has in the past 10 years. However, looking at 5-year periods, the equal-weighted group typically outperforms—meaning that the norm has been the largest capitalization stocks underperforming in most historical periods going back to 1930.

The recent run in large cap stocks has meant that most stocks have underperformed the S&P 500. In both 2023 and 2024, less than 30% of stocks beat the cap-weighted index, hardly a good environ- ment for stockpicking.

As Stein’s Law states, “If it cannot go on forever, it will stop.” In our view, this applies to the ongoing outperformance of the megacaps. We believe that the performance bias towards large cap stocks will subside or even swing back to the historical norm of smaller cap stocks outperforming. High valuations and low dividend yields make the current crop of megacaps unappealing to dividend investors. Once total returns broaden, we would expect dividend-focused portfolios to perform well against the S&P 500.

Read more hedge fund letters here