Hayden Capital commentary for the second quarter ended June 30, 2025.

Dear Partners and Friends,

Our portfolio had a strong quarter, as geopolitical anxiety subsided the past few months.

The markets quickly realized that Trump’s initial tariff threats were simply an opening salvo in the “Art of the Deal” – as newly negotiated rates are coming in at just half what was proposed a few months ago. Markets let out a sigh of relief.

As an unintended consequence, emerging market assets are finally catching a bid. This whole saga highlighted just how erratic and unreliable a partner the US has become, to its global peers. US assets have typically commanded a premium due to its rule-of-law and perceived safety of assets. But if the US government is behaving like an emerging market anyways, why not invest closer to home, where valuations are lower3?

The MSCI Emerging Markets index is outperforming the S&P 500 by ~9% year-to-date4. If this continues, it will be the first time emerging markets have outperformed the US since 2017.

**

During these last few months, I’ve also had more conversations with investors at other investment firms – part of searching for new opportunities shaken out by recent market volatility.

While the conversations have been fruitful, I couldn’t help but notice just how often other investors talk about their “long-term” investments as measured in quarters, nowadays. Investing with a 3-year outlook (let alone owning companies for 5 or 10 years, like we aim to do) is starting to feel like a relic of the past.

Combined with the rise of pod shops, 0-day options, and meme stocks – it just feels like we’re living in an alternate reality than the Efficient Market Hypothesis would have predicted.

And I certainly sympathize with the underlying cause – the phenomenal performance of Mag7 leading to a US-centric focus, the institutional need for volatility dampening (or more accurately “volatility laundering”?), and lower social mobility / stagnant career outlooks leading younger generations to gamble their savings as the only hope of creating better lives for themselves (“wen moon”?).

I talked about changing market structures in our Q3 2024 letter last year and the rationale behind it (LINK). And I’ve said many times before, we must adapt to the way the world is, not as we wish it to be.

But that said, as an industry, it feels like we’ve given up on making money alongside the intrinsic growth of businesses, whose ownership just happens to trade publicly. Instead, we’re now just extracting short-term inefficiencies from the public market “machine” itself and are agnostic to the specific tickers fluctuating on it.

Profits are a “tax” on the value that a business creates for society5. This is an infinite game, as long as there’s still problems to be solved in the world. Short-term trading is a zero-sum game, that has limited capacity. At some point, there will be no more short-term inefficiencies to exploit.

It’s starting to feel like this “short-termism” isn’t sustainable. Or maybe I’m just getting old…

**

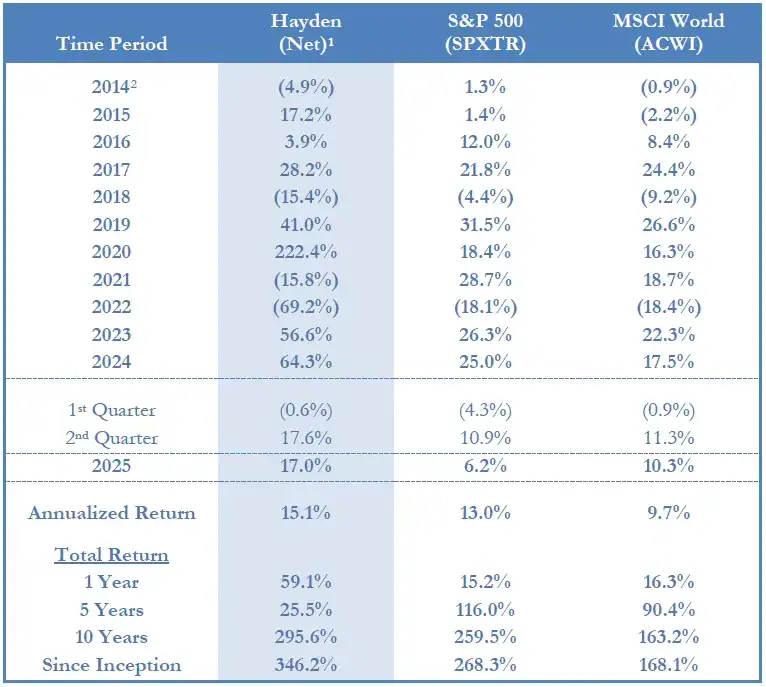

Our portfolio gained +17.6% during the second quarter. This compares to the S&P 500’s +10.9% and MSCI World’s +11.3% returns during the period. Since inception, we have compounded our partners’ capital at +15.1% annualized after fees, versus +13.0% for the S&P 500 and +9.7% for the MSCI World indices.

We continue to find better opportunities internationally, with ~57% of the portfolio in Asia, ~31% in North America, ~10% in Latin America, and the remainder in cash.

Minimax

What is Minimax?

I’ve been reading up more on AI (I know, I know, who isn’t…), and kept coming across this “Minimax” theory. It’s one of the foundational ideas in game-theory and artificial intelligence – so much so, that one of China’s leading AI firms is even named after it (LINK).

So I spent some time reading up on it, a few weeks ago. But it turns out, the more I read, the more I saw its applicability to our own craft / style of investing.

The minimax theory was first proposed by Von Neumann and prescribes an optimal strategy in a two-player zero-sum game. In essence, it assumes you want to maximize your chance of winning, while the opponent will minimize your chances. As such, you should pick the move that gives you the best worst-case outcome (i.e. minimize your maximum possible loss).

At first glance, it can be misinterpreted as picking the move conservative move and avoiding risk at all costs. But that would be wrong.

Instead, there’s a beautiful deeper principal behind it. The theorem states that winning isn’t about total risk elimination. Uncertainty is unavoidable – you can’t perfectly predict what other players (or the world) will do.

The Minimax theory is about surviving. Even if the worst-case scenario happens. It accepts that risks exist, so rather, it channels it. It teaches you to deliberately choose a path where, even if the opponent plays optimally against you, you’re not knocked out.

And by definition if you don’t lose, then you can bide your time until favorable opportunities inevitably arise, and give you an opening to win.

I think poker is a great illustration of this. In poker, the optimal play isn’t to fold every hand to avoid losing (you’d never see the flop). Instead, you should optimize your exposure to ensure any specific losing hand doesn’t take you out early, and having enough bankroll to keep seeing new hands.

Inevitably you’ll find yourself with “the nuts” and can capitalize on these favorable odds to win. But the trick is to stay in the game, grinding it out until then.

**

Applying Minimax to Investment Firms

So how does this relate to investing? And especially in a volatile niche like emerging growth companies?

First off, it reinforces that having a high “survival threshold” is the most important. If your loss tolerance is higher, then your “worst-case survival zone” is wider. Think of this as your personal “margin of safety”.

As such, you’re able to accept strategies that may look too risky for your opponent – but for you, they’re survivable. And since so few can play the game in the first place, the odds of winning (and expected long-term payoff) is higher.

Even the best investors might get it wrong 45% of the time (55% hit rate), so being able to take losses is not a matter of “if”, but of “how much”. You need to maximize for staying in the game, to let organic compounding and time work to your advantage (i.e. time matters more than absolute returns).

For instance, an investor that compounds at 10% a year for 30 years will be worth more than another who generates 30% a year, but is taken out in 10 years (17x returns vs. 14x).

**

But if creating the widest “survival zone” (i.e. tolerance for volatility) is such a large advantage, how do you go about doing that? Why is it that some investment firms can tolerate higher losses than others?

In the professional investment business, I think this ultimately trickles down to the quality of your underlying LPs (“Limited Partner”, i.e. client), and their volatility tolerance.

I’ve talked about this numerous times before, but I think our peers don’t pay enough attention to who they’re partnering with and ensuring 100% alignment between LPs <> Investment Manager <> Investment Style.

Seth Klarman of Baupost said it best, recently commenting: “I want to know that if I think I had a good year, [the LP] will also think it’s a good year. That’s hard to know in advance, but it’s why you get to know people. It’s in everybody’s interest to create that alignment and identify if it’s present. So, we never just take a phone call and have somebody wire money.

We take a meeting and we get to know them. We flood them with our materials. And if they say, “you know, that's all too much”, fine, then it's not a good match.

And the other thing we do is once somebody's in as a client, they can't always anticipate how they're going to feel at different points in their life based on different kinds of investment results. So we try to educate them further as a client.”

Unfortunately, many firms in our industry treat the LP relationship simply as a transaction – i.e. “any sale is a good sale” (let alone continuously investing in the relationship and investor education, as Klarman suggests). But I think this is short-sighted, and they unknowingly give up a foundational investing edge. In essence, they choose AUM growth over returns and, most importantly, duration.

Separately, another way investment firms can increase their business’ margin of safety, is by better managing their costs. I know some investment firms who collect millions in fees, but are barely break-even. Their high office rent, bloated staff payroll, legal fees, etc. leave little room for resiliency and variability in revenues.

And we see this in the statistics, with almost half of hedge funds shutting down within 5 years (LINK). It’s almost never because of performance. But like any other business, because their costs are too high relative to revenues8.

When you partner with an investment firm, you need to underwrite not just their investment process. But also their ability to stay in the game as long as possible, to maximize how long they can “mine” their lucrative investment niche.

If a firm has an aligned and informed LP base (and thus more tolerant of volatility, since they have a better understanding of the underlying risk), this can give you a huge advantage. It opens up completely different games to you, that your competitors can’t touch.

**

Real-time Examples

Most notably, I watched this happen in real-time over the last few years. When many “tourist” investors chased returns into emerging growth stocks during the 2020 and 2021 cycle, and suddenly found themselves structurally unsuited for this type of investing during the 2022 draw-down. Understandably, many vowed afterwards to completely avoid emerging growth companies, simply because the short-term volatility is too high.

But I think this is the wrong lesson – the issue isn’t emerging growth companies themselves. Many of these stocks have more than re-couped their losses and are now leaders in their fields (see our Q1 2025 letter; LINK).

Instead, the problem is these investors weren’t suited to play this game in the first place. Their “survival threshold” (the point at which their LPs lose confidence) is too low, and it was only a matter of time before the strategy’s inherent volatility breached this level. Combine this with high firm overhead, and soon their revenues are running below costs9.

This forced them to sell-off their positions / “exit the game” at exactly the wrong time, and transfer these imbedded profits to more resilient players. Unfortunately for their LPs, this meant permanent capital loss.

**

Going on the Offensive

But what if you had the foresight to structure your firm with a high survival threshold? What now? What’s the best way to use it to your advantage?

Put simply, I think it’s weaponizing your opponents’ risk-aversion.

For example, I talked about how the investment world is shifting towards market-neutral / multi-manager firms (“pod shops”) last year (LINK). By my estimates, these extremely short-duration firms already comprise >50% of hedge fund trading volume.

It’s widely known that these strategies have very tight risk-limits – individual PMs have their capital cut if they’re down -5% and force liquidated after -7.5 - 10%.

Ironically, as more industry assets move in this direction, it creates even more volatility – as too often everyone’s on the same side of the trade. If everyone is sitting on the same side of a boat, it rocks more not less, when waves hit.

For example, 20 years ago, a stock that missed earnings may have fundamentally traded down -10% the next day, as earnings expectations came down. But these days, it’s common to see that same stock down -30%. The first -10% is fundamentally justified, but the other -20% is all the pods caught “off-sides” and stampeding for the exits at once.

As these firms sell and put pressure on the stock price, this then starts triggering automatic “risk limit” liquidations for the others. And in turn, this forced liquidation pushes the stock price even further down (and triggering even more pods to sell, deathly worried about hitting their own risk limits and getting fired).

Essentially, it’s a “cascading margin call”. Worse yet, even if other investors know the stock is down due to irrational reasons, they often can’t step in to take the other side for business reasons. What if irrational selling begets more irrational selling, and the stock is down another -20%? How will you explain that to LPs who thought they were buying a low-volatility strategy?

Every earnings season, we seem to experience more of these and rumors of “pod blow ups”. Whether it’s actually happening or not, it’s clear that the stock market has changed.

Theoretically, the popularity of short-duration strategies should make markets more efficient (and thus less volatile) on a day-to-day basis. But the opposite is happening.

**

Lessons

If you can stomach short-term losses that your opponents can’t, it gives you a lot more playable choices. You can buy into these forced selling situations, since you’re not afraid of losing your job if the stock takes another irrational step down.

Or perhaps it opens up a brand new pool to hunt for new ideas – one where the multi-manager firms can’t play due to the inherent volatility of the business models, lack of alternative data to give foresight on the earnings print (and thus subject to unknown volatility on earnings day), or don’t have the necessary $50-100M daily trading volume necessary to quickly enter & exit positions.

(Note: The latter has been our best source of alpha / new ideas these last few years – where it feels like we have the entire market to ourselves. For example, buying smaller businesses in the $1 - 10BN market cap range and / or going through business model transitions where the near-term earnings outlook is inherently volatile.)

**

Commonly, investors will pitch “small / micro caps” as inefficient areas of the market. But I actually think the emerging growth niche has surpassed these in inefficiency. One relies on size & liquidity as reason for potential alpha (“Fidelity can’t invest in a $100M market cap company”), while the other relies on behavioral & structural flaws (“Millenium won’t buy a stock that’s down -30% post-earnings, even if long-term prospects are attractive”).

Just because a stock’s near-term price is volatile, doesn’t make its long-term business and earning potential riskier.

But investing in the emerging growth niche does require a unique firm structure – one built methodically, and with a more stable capital foundation than others. You need a specialized “ship” to navigate these waves. And because it’s harder to build this, I think the latter is far more capital constrained than the former.

Charlie Munger famously said, “If you can’t stomach a 50% decline in your investment, you shouldn’t be in the stock market.” I’d argue most investment firms fall into that camp today.

I think this flaw is our opportunity – to play the games & “catch the crumbs” that our competitors can’t.

Portfolio Review

SmartRent (SMRT): This quarter, we sold our remaining shares in SmartRent. “Disappointing” is the only way to describe our investment over the last three years.

While shareholders could easily blame it on the macro environment, I think our investment mistake runs much deeper. It was misjudging the people.

We first invested in mid-2022, and were excited by a rapidly growing software business, that was disrupting the multifamily apartment industry. Revenues grew ~+52% y/y the first year of our ownership, and traction continued at ~+41% y/y in 2023. Meanwhile operating margins trended in the right direction, improving from -62% to -18% during that time frame – well on their way to profitability the following year. (See our original investment thesis for more information; LINK).

Starting with smart access (keyless entry), SmartRent had an opportunity to eventually become the “operating system” for multifamily rental operations.

But the problems started as interest rates jumped over the past few years. For their multifamily customers, it became harder to finance & acquire new buildings for their portfolios. SmartRent’s new deployments fell alongside these declining industry transaction volumes.

SmartRent installation costs ~$1,300 per apartment unit, and ~$3 - 8 per month afterwards. Elevated interest rates mattered for a couple reasons. First, new buildings typically install SmartRent after being bought by a customer that uses SmartRent for the rest of their portfolio.

For example, the bulk of SmartRent’s customers are large public REITs or multifamily owners that own >10,000 units. When these customers buy a new 200-unit property, they’re going to install SmartRent to integrate with the rest of their properties, since the technology allows them to efficiently manage the operations and maintenance of their entire portfolio.

Second, the upfront cost of several hundred thousand dollars is considered capex, and financed as part of the property transaction or funded separately with debt. As interest rates rise, it makes it harder to borrow money and the interest burden harder to justify.

But with over $200M on the balance sheet (~1/3rd of total market cap), we were betting that SmartRent had more than enough capital to weather this headwind. In the meantime, they could focus on deploying their backlog, and getting to profitability through pricing increases.

For example, they had ~550K units actively “deployed” in 2022, but also a backlog of over ~850K “committed” units with signed contracts and just waiting to be installed.

However, by early 2024, cracks started appearing in the thesis. We started seeing SmartRent’s institutional customers delay their backlog installations – choosing to conserve cash instead of deploying it in an uncertain real estate environment.

Not only did this affect growth, but also part of our original thesis is that the medium & small sized owners would be spurred to adopt this technology, forced by competition by the large players. These smaller operators tended to pay software rates closer to $8 per unit per month, versus the $3-4 the larger customers were paying.

I always saw signing the large customers as benefitting SmartRent’s brand (i.e. “if Equity Residential is using it, we [a smaller owner] should try it too”), while the real profits would come from higher margin “long-tail” customers. As such, these changes affected SmartRent’s cash flow trajectory.

However, the final straw came when I learned about the board of directors’ disputes with Lucas (SmartRent’s founder), on the interim growth strategy and their subsequent handling of the situation.

Lucas wanted to launch new products to sell to their Top 15 customers (the ones who own >10,000 units), in an effort to grow wallet share / revenues with them. However, this came at the cost of higher R&D and manufacturing costs – a major reason why SmartRent wasn’t profitable yet.

Alternatively, the board wanted to focus on the high-margin software piece, and focus on raising ARPU and renewing their sales effort to grow their customers into the “long-tail” customer base (the ones who pay $8 per month).

I agreed with the board’s strategy, but ultimately disliked their way of handling the situation. I’ll save the gritty details, but effectively the disagreement / lack of goodwill was so large, that Lucas resigned the same day that the board voted in going in a new direction (in July 2024). Obviously, the sudden departure of the founder & long-time CEO isn’t good for anyone.

The company spent six months looking for a replacement and announced a new CEO starting in February 2025. But Shane Paladin lasted a mere 6 weeks, before the board asked him to leave in April 2025. He was then replaced by Frank Martell, who has been on the board for a year. Frank was previously the CEO of LoanDepot, and the CEO of CoreLogic before that.

While I believe the board ultimately made the right decision in bringing Frank into the seat, the manner in which it was handled left a bad taste in our mouth. I’ve met the Chairman of the Board, in-person and over Zoom several times. While I think he and the rest of the board have good intentions and are moving the company in the right direction, I just fear the company doesn’t have enough sense of urgency. There are also a few members of the board where I question if there would be more appropriate replacements.

I do think the fundamental business problems are fixable – but it needs the right people & culture in place. The company needs to move faster, and they just aren’t at this time. As such, we chose to exit our position earlier this year.

I don’t think this is the end of the story for SmartRent, and still believe they’ll reach profitability soon. But given the concentrated nature of our portfolio, we don’t have room for companies who don’t operate at their full potential. So we’ll watch the situation unfold from the sidelines for now, and have reallocated the proceeds into more attractive opportunities.

This mistake cost us -50.3% on the position. We purchased our shares at an average cost of $3.34 and sold them at an average of $1.66. We’ve learned a costly lesson in the misjudgment of people.

Conclusion

I’m currently spending the next few weeks in Asia, with stops in Tokyo, Singapore, Manila, and Hong Kong. I’m excited to visit our companies & the teams behind them, catch up with our industry contacts, and share notes with fellow investors in these regions.

Particularly, I’m looking forward to seeing our long-time partners & meeting a few new ones in the region. Truly, you are the reason Hayden can think and operate differently than the thousands of other investment firms out there. You are the steadfast foundation we stand upon.

I hope we’ve done a good job of setting the right expectations and continuously educating our partners, although I’m sure there’s room for improvement. Invariably, our goals remain the same – to use short-term volatility to realize higher long-term returns.

On that note, I’m also excited to announce that we’re launching a new investment vehicle, to build relationships with more similarly minded partners around the world. We’ll finally be able to accept partners from the European Union, Hong Kong, Japan, India, Australia and New Zealand.

Our partner relationships aren’t transactions – they’re marriages. And we hope for these marriages to last, for the rest of Hayden’s lifetime. Hopefully this new vehicle will allow more partners to marry into the Hayden family (luckily, we practice polygamy).

Please reach out if you are interested in learning more, and possibly joining us as a partner.

**

Also, I’d like to give a shout out to Carl Lu and Raghav Sharma, both of NYU. They interned with us this summer, and spent their time uncovering potential investments globally.

I wish them both well, as they continue their investing careers.

**

Lastly, I enjoyed this other quote from Seth Klarman’s recent podcast interview, so figured I’d share it here:

“[In the 1980’s] Firms like mine came into business to pick up crumbs left by the elephants. You had giant firms like Fidelity and Putnam and State Street… And they followed a certain regimen, and things fell through the cracks that they just didn't care about making the last few dollars in an arbitrage. It needed to look a certain way to be in their portfolio, and things that didn't look and fit fell behind. But over time, smaller firms have come along to run circles around the larger firms…

So there'll always be minnows that grow up and whales that are getting too complacent. That's going to be true in any market situation where there's human touch, where there's inefficiencies. The inefficiencies get cleaned up over time, but new ones form because of institutional constraints or because of the nature of the market…”

– Seth Klarman (CEO of Baupost), on Value Investing Legends Podcast (LINK)

It reminds me of what a smart friend once said – that the hedge fund industry used to be pirates (i.e. in the 1980’s, when Baupost first formed). Opportunistically going to the ends of the earth, in pursuit of treasure wherever that may be.

But somewhere along the way, we became the Navy – losing our scrappiness, daringness, and willingness to break the mold. As an industry, we need to go back to our roots.

So here’s to treasure hunting. Long live the pirates.

Sincerely,

Fred Liu, CFA

Managing Partner

Read more hedge fund letters here