“With the yield curve (3-month Treasury Bill vs. 10-year Treasury Note) now inverted on a more sustained basis, one can expect more downward pressure on equities, more volatility and more credit spread widening.” – David Rosenberg, Chief Economist & Strategist, Gluskin Sheff + Associates, “Breakfast with Dave” (May 30, 2019)

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

William R. White was Head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the Bank for International Settlements. The BIS is an international financial institution owned by the central banks. It is the central banks’ central bank.

William predicted the financial crisis of 2007-2010 before 2007’s subprime mortgage meltdown. He was one of the critics of Alan Greenspan’s theory of the role of monetary policy as early as 1996. He challenged the former Federal Reserve chairman’s view that central bankers cannot effectively slow the causes of asset bubbles. On August 28, 2003, he took his argument directly to Greenspan. William recommended to “raise interest rates when credit expands too fast and force banks to build up cash cushions in fat times to use in lean years.” Greenspan was unconvinced that this would work and said, “There has never been an instance, of which I’m aware, that leaning against the wind was successfully done.” He should have leaned!

This week I offer you Part III of what I believe will be a six-week series sharing my high level notes from the Mauldin Economics 2019 Strategic Investment Conference. William R. White is important.

Before we jump in, I had a number of thoughtful questions from last week’s On My Radar post (notes from David Rosenberg’s presentation). David concluded interest rates are headed lower and the economy and the equity markets sit in the top of the 9th inning with one out. We sit late cycle. David’s turned bearish.

From a reader: “Steve, as always, thanks for OMR; I enjoy it each week. I’m somewhat puzzled by a couple of things at the moment:

(1) I’ve been hearing about a super bubble in bonds, and yet this presentation from DR says that long-term government bonds are where it’s at; is there a way to put these two together?”

My answer: Yes. Bubbles can grow bigger and last longer than many may expect. When recession approaches corporate bonds, especially HY and leveraged loans will sell off hard (yields will rise), but government debt will rally (lower yields higher prices) as flight to safety. At some point, the exit to the debt mess is monetization. New laws will be required; this is the “debt jubilee” Rosie is talking about. It will likely be inflationary and rates will then move higher. That’s likely path #1 to higher rates. We are a number of years from such event in my view. Path #2 is a loss in confidence placed in governments… there can be a number of reasons for this but the desire to no longer fund government debt will cause bond selling that will drive rates higher. In Europe, they are closest to such event due to political dysfunction/fractured EU structure. Watch Italy and watch the banks. Overall, current conditions are deflationary (aging developed world demographics and high debt levels are a drag on growth) so Rosie sees rates heading lower.

(2) “It seems crazy that interest rates have been so low for so long, i.e. the Fed increasing rates last year seemed long overdue… how do we put this together with the idea that rates are too high, i.e. the Fed ‘did it again?’”

My answer: The Fed has a near-perfect record of screwing up (over tightening). Same this cycle but this time they have far less wiggle room. The 10’s vs. 3-month Treasury yield curve has inverted and if we factor in QT (something brand new to the mix since last recession) it’s been inverted for more than six months. That means we are likely within 6-9 months from recession. Buckle up!

(3) “Steve- I’m trying to understand “Jubilee” and it’s relations to Capitalism. As an old Jewish moral tradition, I understand forgiveness of debt, freedom from financial oppression, release of prisoners, and those in financial bondage. But, explain how this gets me back to 10-yr Treasury notes, and investment in VIX? Jubilee-Capitalism?”

My answer: Jubilee is years off (best guess by late 2020’s). Until then, the Fed and other global central banks will likely stick to traditional Fed reaction functions: lowering rates and on (the relatively newer tool) QE. Debt remains the dominant drag on growth and the aging demographics in the developed world are also a drag on growth.

New laws will need to be passed to permit and enable a jubilee. Depending on the timing and degree of balance (debt is deflationary and dropping helicopter money into the system is inflationary) and how well US policy is in sync with other developed countries… will ultimately determine the outcome. So for now the deflationary pressures rule the game, thus the call for lower rates.

I favor watching the Zweig Bond Model to play Treasurys. To me, the trend in price is most important. Currently, the ZBM is in a buy signal favoring longer duration Treasurys. Fundamentally, I’m in agreement with Hunt and Rosenberg and, right now, the trend in price supports that view. Separately, the trend in HY market is down. HY remains in a sell (lower prices higher yields). I’m keeping a really close eye on both indicators.

So grab a coffee and find your favorite chair. My bullet point summary notes and charts follow. William White began his presentation with strong statement, “My first point is that mainstream macro, as practiced by IMF and the OECD and the central banks, all of which I’ve been associated with, is absolutely fundamentally flawed and that’s the problem. Underlying it all is an analytical, almost a philosophical problem. They have a different view about how the world works than how the world does actually work.” You’ll find my select notes from his presentation. You’ll also find the Zweig Bond Model (and how it works) in Trade Signals when you click through. I hope you find it helpful. Please let me know if you have any questions.

If a friend forwarded this email to you and you’d like to be on the weekly list, you can sign up to receive my free On My Radar letter here.

Follow me on Twitter @SBlumenthalCMG

Included in this week’s On My Radar:

- Mauldin SIC 2019: William R. White

- Trade Signals – Sell in May Back in Form

- Personal Note – Entrepreneurial Leader

Mauldin SIC 2019: William R. White

Before we jump into William White’s presentation, let’s take a quick look back at the last two letters, which highlighted Lacy Hunt and David Rosenberg.

The prior two letters concluded with the following:

Lacy Hunt, Ph.D.: What’s going to happen?

- I [Lacy Hunt] think we are going back to zero bound (Fed Funds rate to zero percent). Because we expect velocity to fall and we are concerned that we will be stuck in a quagmire with a zero percent bond for some time. Yield curve will be a lot flatter. His fund has greater than 20-year duration.

- It will be ugly economically.

- We are not going to get growth. We are not at the end of the declining rate cycle… we haven’t seen the low in yields. He favors investing in long-term government bonds for total return.

David Rosenberg: What’s going to happen?

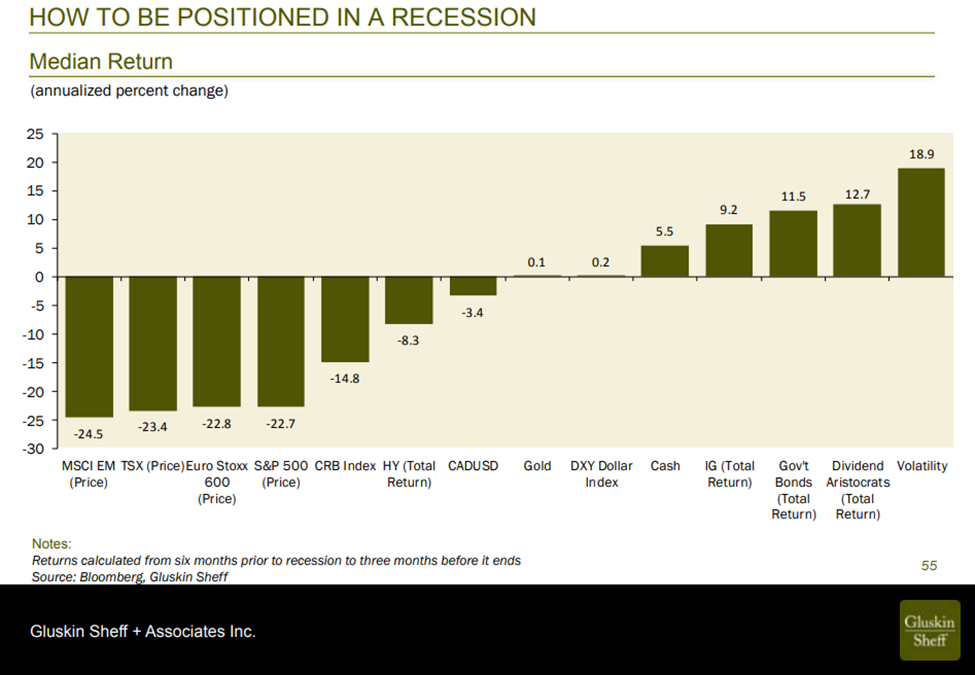

Rosie argues that recession is coming, rates are heading lower and we will move to even more unconventional Fed policy. He recommends the following asset classes will outperform (see next chart) and suggested that the 10-year Treasury may earn a total return of more than 11% over the coming 12 months. He also likes quality dividend payers and going long volatility. For non-geeks, that is a bet that volatility will pick up to the downside (it will get very bumpy) and a way to play that for profit is to invest in the VIX. My dad would say, a play that is “not for the faint of heart.”

Rosie shared this slide:

Notes and Charts:

“In the end the only way out of this mess is inflation.” – William R. White, Former Head of the Monetary and Economic Department, Bank for International Settlements

What will the next crisis bring? How will the debt cycle end?

My bullet point notes follow. Bold emphasis is mine. Prints long but reads quickly.

William’s presentation: “The Flaws in both Theory and Practice.” Here we go:

- I think we’ve had flawed theory that’s been behind the decisions that the central bankers have made and I think the flawed theory has led to flawed policy, both before and after the crisis and

- I think that flawed policy is going to lead to the next crisis.

- The question is what will the crisis look like? And I know that John (Mauldin) and many others have been talking about Japanification, I think that’s possible, but I think there’s also a still darker outcome that we could think about which is one of very high inflation or deflation –

- high inflation or even hyperinflation and it might seem a lot to sort of ask people to wrap their minds around the transition.

We have had non-inflationary boom and I guess what I predict next is we’re going to have

- A debt deflationary bust but what that might morph into is high inflation or even hyperinflation.

- Larry Summers said something years and years ago, which I really liked… We are so used to thinking in linear way, right, and all the models are all linearized as well. He started off by saying one, two, three, what comes next? And the answer is obvious, it’s four. He said, well, not so fast, it could be three because the best predictor of tomorrow is always today. So, not so fast, it could be two, because in the end, everything has this tendency to revert to the mean. He said not so fast, it could be one, because in the end, everything that goes around comes around and that’s the way the world works.

Now I want to say a few words about how these sort of processes of transition are going to work. My first point is that mainstream macro, as practiced by IMF and the OECD and the central banks, all of which I’ve been associated with

- Is absolutely fundamentally flawed and that’s the problem. Underlying it all is an analytical, almost a philosophical problem. (emphasis mine)

- They have a different view about how the world works than how the word does actually work and my first bullet point makes this point as clearly as you can do.

- In the spring of 2008, the wheel, the IMF wheel forecasted growth in the advanced market economies in 2009 would be 3.8%, and it came in at -3.7%, probably the biggest forecast error in history.

- None of these conventional mainstream people saw this thing coming, okay, keep that in mind.

- And, subsequently, we’ve had nine years in a row of the IMF and the OECD basically forecasting, a big rebound in growth and a rebound in inflation next year.

- They did that nine years in a row without having a fundamental rethink about whether the models were right.

- So, I just want to get this idea firmly in your head, there’s something — there’s something wrong here. Now, the question is what is it that’s wrong?

- They think about the economy as a machine, okay, that’s sort of on autopilot. Whenever anything goes wrong, this machine goes back to the level of operation that it was at before. It seeks a kind of equilibrium.

- So, if the unemployment rate goes up, for whatever reason, the economy will sort of go back to full employment.

- That’s not the way the world works. The world doesn’t have an equilibrium and the world is not linear in the sense that everything moves in small discrete movements.

- The fundamental problem with these models is that they ignore all of the stuff that’s really interesting. So, when you — when you get into them, these models have no money in them, they’ve got no credit in them, they’ve got no debt in them, they’ve got no bankruptcy in them. These’re all the things that are really interesting.

- And it’s the interaction between all those things that lead to the nonlinear outcomes, the booms and the busts, that basically all of us are sort of interested in. And I just note, and this is the last bullet about the fundamental temporal inconsistency. In these models, if you leave out debt, and you leave out debt accumulation, you say I’ve got a downturn in the economy, sort of think 1990. I’ve got a downturn in the economy, I’m going to lower interest rates and that’s going to kick start the economy and, indeed it did.

- But the whole point is that it kick started it by inducing people, both corporations and consumers, to borrow more money to spend today. But if you’re moving your spending from tomorrow to today, building up debt, this is a headwind which slows down consumption and investment.

- And the point of the matter is, you do it in 1990 and it works, you do it again in 1997, and it works less well. You do it in 2001 and it works still less well. So, the monetary policy has to get more and more aggressive to achieve the same outcome as it did right at the beginning.

- There is a fundamental intertemporal inconsistency. It works at the beginning but you do more and more of it and as the debt builds up, it fails to work at the end and that is precisely where we are heading.

- So, when you look at what happened prior to the great financial crisis, flawed policies based on flawed theory, for a starter, the kind of models that these folks use because they leave out all the stuff that’s interesting, like credit and debt, the only indicator that’s in there of something could go wrong, the only indicator that’s in there is inflation.

- And so you get this pervasive emphasis on what is inflation doing and this very odd overreaction to points of a decimal deviation from desired price levels brings all sorts of major, major policy changes.

- Well, the first thing that happened prior to the crisis was that this preoccupation with price stability led the central banks to completely ignore the issues of why prices might be going down. And why prices were going down prior to the great crisis and the central banks totally missed it was basically because of China and India and Slovakia and the baby boomers all interacting to increase aggregate supply.

- They should’ve let the prices go down because that’s what the prices wanted to do in the face of a productivity increase, but they didn’t do it.

- And so, the upshot was that we had cycle after cycle of basically asymmetric monetary policy. Every time there was a problem, the interest rates went down and they could do that because there was no inflation. But then when the economy recovered, the interest rates never went back up again to the amount that they went down before, both in nominal and real terms because they didn’t have to because there was no inflation.

- That asymmetric monetary policy, I think, was wrong.

- In the United States and in so many other countries, you get into a downturn, you get the automatic stabilizers, you get the discretionary fiscal stimulus and that’s all fine, but then you get into the upturn and nobody ever tightens to the same degree that they eased.

- So now, in addition to debt building up, private debt, cycle after cycle because of the asymmetric monetary policy, now we got sovereign debts building up cycle after cycle because of the asymmetric fiscal policy and that just sort of adds, sort of fuel to the fire inadequate structural reforms.

- And we are starting, just starting to see this now. The great moderation prior to the crisis, everything was great, there was no problem. If there is no problem, there is no need for a solution. Nothing needed to be fixed.

- So, this creeping monopolization, which has been going on and we talked about this in a couple of sessions yesterday, you know, monopolization, cartelization, nobody paid any attention to it and now we are starting to see it’s a problem.

- The second thing during that period nobody paid any attention to was distributional issues and inclusive growth. Something could have been done in that pre-crisis period, but it did not have to be, because everything looked really, really good.

- And lastly of course the excessive deregulation of the financial system. You know, light-touch supervision, constant deregulation in the financial system, absolute encouragement for everybody to go for it, and indeed, that’s exactly what they did.

- So, we had flawed policies before the great financial crisis and I think we’ve had flawed policy since.

- What’s happened, think about it – the last 10 years is more of the same.

- We had ultra-easy, we had unnaturally easy monetary policy prior to the crisis and now we’ve had ultra-easy monetary policy after the crisis.

- It’s been more of the same of the stuff that brought the crisis in the first place. So, you can see, how this is all likely to end.

- I want to make the point that the initial global response to the crisis was perfectly sensible. We had monetary easing, we had QE1, but the point was all of that was premised on the problem being financial instability. Remember, in 2008-2009, markets just basically collapsed, alright. Everything just stopped happening and the central banks quite rightly went in there and said this is a liquidity problem. The central banks are in the liquidity business, we’re going to sort this out and they did.

- So, the first thing that they did was totally appropriate. After that, things morphed and I can remember reading Ben Bernanke’s speech, I think to The Economics Club of New York in 2010, when he sort of announced QE2 and the thought that went through my mind is, he is announcing the same problem but with a different objective in mind.

- So, the initial Q1 was all about financial stability, QE2, and subsequently was all about stimulating aggregate demand and that was a very, very different thing. And we’ve had 10 years of it, and in a certain way, the central banks did what they did in part because – to use that expression, they were the only game in town.

- Everything went into the direction of really restraining demand in the interest of making future financial system more stable. So, everything’s going in the wrong direction, except monetary policy. So, monetary policy, was kept at it, you know, QE2, QE3, forward guidance, Operation Twist, negative interest rates in Europe, okay? We pulled out all the guns.

- The problem was that it’s been remarkably ineffective. So, we have had 10 years, I remind you, we have had 10 years of negative real interest rates in the United States and many other countries as well, not least Europe and Japan, okay?

- Now, you want to think about that. Because the monetary policy was ineffective and it didn’t get the economy growing again, they’ve kept at it for 10 years or more and what has happened on the side?

- The side is that all of the things that aren’t in the model were building up in accumulative fashion to cause the kind of problems that we were all going to be facing going forward – dangerous side effects have got many manifestations.

- The most important one is the debt that is going to come back and bite us in the bum.

- But I also make the point, there is an awful lot of other imbalances have been building up over the course of the last 10 years, one of which clearly is asset prices. There have been so many references to that, US equities, the yields on triple D’s, the VIX, the unicorns, Uber. House prices in many countries, my own Canada. We heard Grant Williams yesterday talk about Australia. I was listening to him saying wait a minute, wait a minute – this is Canada, this is New Zealand, this is Australia, this is the Nordics, this is Israel, there’s a lot of countries out there that have got these problems.

- Asset prices are also a part of it. Financial market malfunctioning. There’s been no price discovery in many of these markets for years.

- The BOJ (Bank of Japan), in some cases in Japan there have been no trades in JGBs (Japanese Bonds) on any given day. This is extraordinary.

- We have had this whole period of risk, you know, switching back and forth, risk on, risk off. This stuff is not normal. What happened to diversification? What happened to value investment? All these flash crashes and now we’ve got concern about liquidity.

- I know John Mauldin’s been writing about this a lot. Concerns about liquidity going forward. So it’s not that, it’s asset prices, it’s financial market mis-functioning, threats to financial stability, okay?

- There is something going fundamentally wrong here where you’ve got all of the regulators doing what they are doing to sort of increase financial stability, but think of what ultra-easy monetary policy is doing to the behavior of the financial institutions.

- These guys have got to go for yield, because the basic business model, which is margins, the margins have been getting squeezed and squeezed and if you think it’s bad for the banks, think about the poor insurance companies and the pension funds, okay, who are already facing the big problems with demographics, okay? And now we’ve have added the squeeze of the margins too.

- So, I think, honestly, that these policies have actually led more to financial instability than financial stability. And lastly, of course, in terms of imbalances and we’ve talked about this earlier on is the threats to growth, that we’ve got all these zombie banks and these zombie companies, all sitting out there, in a certain sense excess productive capacity driving down the prices, maybe even inducing the Fed to ease still further, because the prices aren’t going up.

-

- But they are not going up because of the policies that the central banks have been following.

- So, flawed policies, both before and after.

- I think a further stage in this crisis is inevitable and I’m not saying anything that’s widely different from what you’ve heard from many other speakers.

- How will it come about?

- It could be a trigger, okay, it could be an exogenous shock to the system. Trade wars are a very good example.

- I was struck yesterday that — pointing out the fact that we’ve got all of these financial imbalances and that think about triple B’s and all that stuff, you know the corporates and we had a number of people saying all of the analysts are starting to say now that the corporations have got to do something about leverage and they are starting to try to do something about leverage and what that something might be is that they are going to cut investment.

- But if they cut investment, when they weren’t investing very much in the past, we’ve got a real problem, that really is Japanification, that’s going to be a balance sheet recession and it could be triggered trade wars, Hoot-Smalley 1932, you know. It could be something exogenous that does it.

- But having said that, all of these imbalances that I’ve been talking about, these things that are unnatural, somebody said earlier on, Herb Stein, “if something’s unsustainable, it will stop.”

- Any one of those imbalances could actually be the trigger for the next and they are all out there lurking, waiting to happen.

- But one thing we do know for sure is that when the downturn starts, all of those imbalances are going to amplify it.

- So, whatever sort of causes things to happen, the asset prices will start to move, the debt yields will start to go. Stuff will happen that will amplify the downturn and I would note in the world in which we live, the globalized world in which we live, problems anywhere are problems everywhere.

- So, you think about 2009. 2009 we had a problem in the United States, to start with, right, subprime. What happened in 2009 was investment globally collapsed. Investment everywhere collapsed.

- Problems anywhere are problems everywhere. And for those of you who think the financial system is invulnerable now because of the all of the effort Dodd Frank and blah, blah, blah, that’s gone into the post crisis reform agenda, I just put it to you, think again.

- I’ve just written a 30-page paper on this stuff about evaluating post crisis regulation and if you think we’re out of the woods, we are not.

- One of the fundamental problems is the bad loan problem — the old bad loan problem, maybe outside of the United States was never fully resolved, okay?

- The Europeans never came to grips with the bad loan problem in the banking system and we’ve had all sorts of new loans, let’s talk China and, you know, just this morning I was reading the Financial Times. Two-thirds of the growth and consumption in China is in the household sector, now for the good news. Bad news is a very large amount of it was financed with a big increase in household debt, okay.

- So, the financial system remains vulnerable, too big to fail. All the talk, we’ve never sorted that out. I’ve never talked to anybody who is knowledgeable about too big to fail, who will say we’ve sorted out all of the problems.

- I’m confident that if we let J.P. Morgan go under that it won’t start a world crisis, I’ve never heard anybody say that.

- And so the bottom line, I think is that debt deflation threatens because once these cumulative processes get started based on debt that’s the way the whole thing tends to work.

- And if the problems that we face are bigger than the ones that I think we faced in the past, our capacity to respond is now significantly reduced.

- And again, I don’t have to tell anything you don’t know if you think about the crisis management tools, okay?

- Last time we used monetary policy, interest rates were much higher. Now the interest rates are pretty close to zero in most places, are actually negative in many others.

- The size of the balance sheets are much larger: In the United States, the Fed’s balance sheet is 20% of GDP, in Europe, the ECB is 40% of GDP, in Japan, the BOJ is 100% of GDP.

- There may still be room but it’s going to be much more limited room than in the past and on the fiscal side, the degree to which sovereign debt ratios in the advanced countries have ballooned, incredible.

- So, it’s going to be more limited, and what I worry about, and I’ll just throw this out is liquidity support, okay. The last time around, remember what I said at the beginning of the crisis, the central banks reacted in the right way. Dodd-Frank has got six separate provisions in it that will prevent the Fed from doing next time what they did the last time.

- The last time, the Fed lent a trillion dollars to foreigners through the discount window here and through the swap lines and I just sort of throw it out. Is the Fed going to be prepared in the current political environment to hand out 1 million, 2 million of swaps or discount support to these untrustworthy foreigners? We got some issues out there.

- Crisis resolution tools are inadequate.

- When you get a crisis, there are three phases. There is crisis prevention, then there is crisis management, then there is crisis resolution. Crisis resolution comes down to — we’ve got a big debt problem.

- The debts are going to have to be restructured, written off, whatever and then we move on.

- The OECD, the IMF, the G-30 in recent months have all written big pieces basically saying that our capacity to do that globally is not adequate.

- The US is probably further ahead than anybody else in terms of vulture funds and markets where debt that’s not going to be, you know, not serviced as it’s supposed to be but there’s — there’s real issues out there.

- And frankly, the question I ask policy makers, I should say policymakers should have focused on crisis resolution ages ago and they never did, and of course, one of the reasons why is because people like you in this room, often with political influence, you don’t want to talk about the fact that the money is gone. So, there’s a huge, sort of tendency to forebear and I guess my sense of it, is that given where we are, we can’t rule out a worst outcome than in 2008.

- What are the policymakers going to do?

- I think they’re going to double down and I think they’re going to double down for all sorts of reasons.

- There has been no paradigm shift in the basic analytical framework, you know, the way these people think about how the world works.

- I discern no fundamental change in the way they think about the world and they’re going to double down because that’s what they think will work in spite of the fact that it hasn’t worked over the course of the last 10 years.

- There is a natural unwillingness to admit past mistakes. They’ve done what they have done. I think it’s contributed materially to the problems we face going forward. They can’t say that and they won’t say it. It’s an admission of guilt and they’re not going to do it.

- Something must be done. This is natural, there’ll be huge political pressures, something must be done and doubling down is something.

- I think there’ll be a lot more monetary easing or attempts at easing that won’t work. This time around, there’ll be a lot more on the fiscal side and I know this worries John Mauldin and many people in this room but that’s what’s going to happen.

- There’ll be a lot more emphasis on the fiscal side. Many, many people are calling for it, I mean the OECD, the IMF, they’re all saying you made a mistake not to use more fiscal last time, don’t make the same mistake again.

- And the last thing, and I find this very worrisome, is modern monetary theory and we will come back to this in the panel discussion – modern monetary theory.

- Short-term, what they are suggesting is exactly what the IMF and the OECD people are suggesting, you know, Larry Summers and Jason Furman and all sorts of thoughtful people.

- What they’re suggesting is you use fiscal expansion and the central bank prints the money, alright. So, in the short-term, this is going to be as it were — the buying set is going to support, what I have said they’re going to do, the doubling down, particularly on the fiscal side.

- I believe that saying that we don’t have a longer-term problem of fiscal excess is a big mistake. So, I think they’re going to double down.

- Now, what’s going to happen?

- Frankly, if we have a crisis, it’s going to be an unhappy outcome, okay. However this thing works out, it’s going to be an unhappy outcome.

- It’s going to be boom, bust, end of story.

- But the really interesting question with big investment implications is which particular path of unhappiness we’re going to go down and the better story and I think this is John’s (Mauldin) sort of story.

- The less unhappy outcome is we’ve got all this fiscal and monetary stimulus and it will work, okay. This is all by assumption, it’ll work and indeed it may work so well that you’ll actually turn the inflation thing around and we’ll get a moderate degree of inflation.

- The less unhappy story is the growth rate exceeds the interest rate and so if you can do this long enough, you gradually eat away at the debt burden and that’s what went on after the Second World War and Carmen (Reinhart) will probably talk about this later.

- At a certain point, people will see the writing on the wall, okay? And they will say this kind of monetary expansion against the back drop of the huge financial deficits can only end in hyperinflation and currency flight, this Sargent Wallace and Ben Holtz, these are just people that have both thought about the theory and the practice about what happens.

- It’s happened many, many times before. Currency flight is typical. I don’t think the dollar is vulnerable in the short end, I’m more with those people who say this time around, the dollar will probably continue to be the safe haven, but the safe haven status is becoming more and more problematic as the fiscal deficit grows, so I think we’ve got one more kick at the can, but it’s getting more and more problematic.

- And this is my last point: politics and geopolitics.

- If these unhappy stories unfold and particularly the more unhappy outcome, there’s going to be a lot of domestic political instability and there’ll be a lot of international political confrontation.

- So, all I can advise to you, as you sort of think your way through (the outcome I see) first the deflation and then maybe the inflation, is to also put a lot more emphasis on the geopolitical stuff, because increasingly, as George Friedman was saying yesterday, that’s where the action is going to be taking place.

- But since it’s an unhappy story that I’m telling today, I guess the only thing I can finish with is – good luck. You’re probably going to need it.

On that depression note, I do want to leave you with a sense of optimism. Crisis creates opportunity. Have a plan in place to manage your assets from here to opportunity and seek special opportunities as they do exist. Lean on a trusted and deep network. Rosie favors trading strategies (as do I) and longer-duration Treasury bonds and high dividend, high quality stocks. It’s a question of how you position. Today, more defense than offense… with a game plan in place.

Coming up next week: We’ll continue the Mauldin SIC series over the next three weeks and I’ll then conclude the series with my thoughts, key takeaways and select ideas to hopefully help you (and me) better navigate the path ahead.

Trade Signals – Sell in May Back in Form

May 29, 2019

S&P 500 Index — 2,783

Notable this week:

No changes in signals since last week’s post. Notwithstanding significant geopolitical risks, such as the latest chapter in the US-China trade war and elevated risk of conflict in the Middle East, equity and fixed income market indicators remain bullish. We note the Ned Davis Research Daily Trading Sentiment Composite remains in the mid-30’s, indicating “extreme pessimism,” which is typically (and counter-intuitively) short-term bullish for the S&P 500 Index. The Don’t Fight the Tape or the Fed remains at a bullish “+1” signal. The Daily Gold Model, however, moved to a sell signal last week.

So far, “Sell in May and Go Away” appears to be back in form.

Click here for this week’s Trade Signals.

Important note: Not a recommendation for you to buy or sell any security. For information purposes only. Please talk with your advisor about needs, goals, time horizon and risk tolerances.

Personal Note – Entrepreneurial Leader

“I probably got my greatest lessons on leadership when I was in the Marine Corps,” he said. “As a little example, the highest ranking officers in Marine Corps always were last in the chow line. That’s the kind of leadership I learned.” – William H. Donaldson

The highlight of the week was time with William Donaldson in NYC. His son Matthew arranged a book signing event Wednesday evening at the Yale Club. William was the 27th Chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), serving from February 2003 to June 2005. He served as Under Secretary of State for International Security Affairs in the Nixon Administration, as a special adviser to Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, Chairman and CEO of the New York Stock Exchange, and Chairman, President and CEO of Aetna. Donaldson founded Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette.

Donaldson attended both Yale University (B.A. 1953) and Harvard University (M.B.A. 1958). While he was a senior at Yale, he joined its Skull and Bones secret society. Donaldson returned to Yale and founded the Yale School of Management, where he served as dean and professor of management studies. Donaldson had a vision of Yale’s management program forming students who could easily and seamlessly flow between public and private management roles. (Source)

To say I was excited to meet Mr. Donaldson is an understatement. A special hat tip to his son Matt (thank you) and to Rory Riggs and his team at Syntax who hosted the event.

Following are a few photos.

And I leave you with a heartwarming story. Rory and his wife Margaret had lunch the prior day with William and his wife Jane. Jane and Rory learned that both of their fathers played football together at the University of Illinois in the late 1930’s to early 40’s. Tom Riggs was a World War II battalion commander who was captured by the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge, then escaped and struck out on a desperate odyssey to rejoin his unit. As Rory said, “Could you imagine our fathers having beer together on a Saturday night after a football victory saying you know one day our children are going to meet?” Had the two men had any idea about what was about to unfold and the role they played in the world. The Greatest Generation!

You can find William Donaldson’s book, Entrepreneurial Leader: A Lifetime of Adventures in Business, Education, and Government on Amazon. I’ll be reading it this weekend.

A quick aside, the Nasdaq is hosting an online webinar on Thursday, June 6, from 1:00 pm to 4:00 pm ET. I’ll be speaking on “How to Use Managed Accounts in Portfolio Construction.” Registration is for financial professionals only (event will qualify for 3 CFP, IWI, CFA CE credits). You can register for the Nasdaq webinar here.

Best to you and your family. Have a great weekend!

Best regards,

Stephen B. Blumenthal

Executive Chairman & CIO