RV Capital Co-Investor Letter for the first half ended June 30, 2024.

Dear Co-Investors,

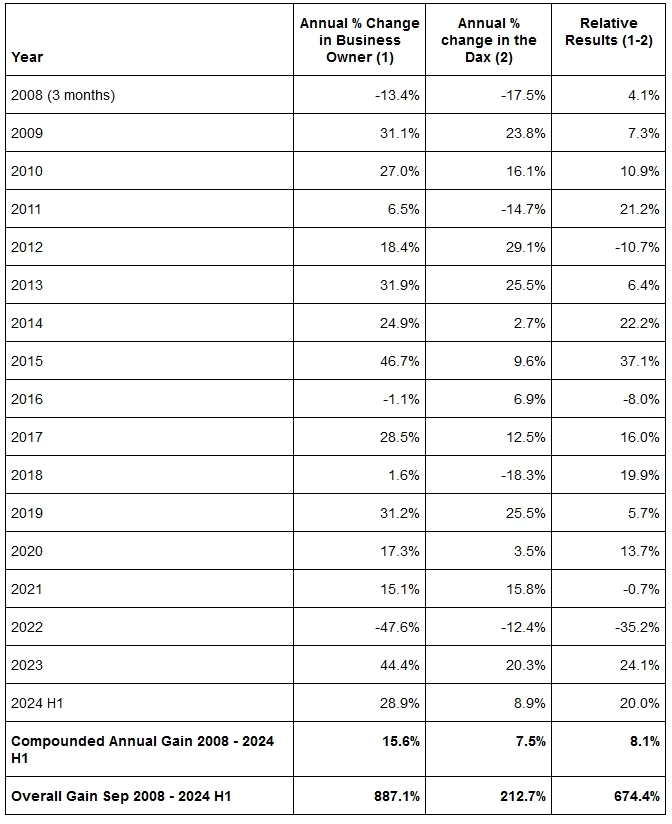

The NAV of the Business Owner Fund was €979.45 as of 30 June 2024. It increased by 28.9% since the start of the year and by 887.1% since its inception on 30 September 2008. The compound annual growth rate since inception is 15.6%.

Read more hedge fund letters here

A New KVG for the Business Owner Fund

At the investor meeting in Bonn this year, Norman Rentrop communicated his decision to close the Investmentaktiengesellschaft für langfristige Investoren (“InvAG”). The InvAG is the investment manager of the Business Owner Fund, and RV Capital is its advisor — or, to be precise, sub-advisor.

Like many others, I am sad that an era is approaching its end, but my overwhelming sense is one of gratitude. I will discuss this further shortly.

The most pressing question for investors in the Business Owner is likely what this means for them. My expectation is that nothing significant will change. RV Capital will continue to advise the Business Owner fund. The fund's name and ISIN will remain unchanged. Its running costs will not increase and may even fall a bit. The fund’s high-water mark will remain unchanged. The transfer has no tax consequences. My expectation is that investors will not notice any substantive differences. Investors do not have to do anything if they want to stay in the fund and will receive an official letter explaining the transfer in the next few weeks.

The InvAG intends to transfer the management of the Business Owner Fund to Axxion. Axxion S.A. is a Luxembourg-based investment manager (Kapitalverwaltungsgesellschaft or “KVG” in German) that specializes in providing service for funds such as the Business Owner Fund. Many large and well-known independent funds use Axxion as their KVG. I have gotten to know Axxion over the last year or so and am delighted about the choice.

All the parties concerned are working to complete the transfer as quickly and seamlessly as possible. Completion is planned for 31 December 2024.

Thank You

As my association with the InvAG approaches its end, my overwhelming sense is one of gratitude. I am grateful to Jens Grosse-Allermann and Waldemar Lokotsch, who, as co-CEOs of the InvAG, were instrumental in setting it up and making it the successful organization it became. I am also grateful to Janine Fitzenreiter and Tanja Titz, who provided a near round-the-clock service in the back office to ensure that orders were placed in a timely manner and the administration of the fund worked seamlessly.

Above all, though, I am grateful to Norman Rentrop, or “Herr Rentrop” as I know him. Herr Rentrop is the founder and sole shareholder of the InvAG, so without him, there would be no Business Owner Fund. However, the role he has played in my development extends far beyond the InvAG. To illustrate this, allow me to recount my journey as an investor and entrepreneur.

I founded RV Capital in July 2006, two months after attending the Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Meeting for the first time and six months after the birth of my second daughter. I think it is fair to say that I am not one of life’s natural-born entrepreneurs. When I hear anecdotes about founders maxing out their fifth credit card to bootstrap their startup, a shudder goes down my spine. I nevertheless took the jump into the unknown, likely due to the confluence of three unrelated events.

I had had success managing my money up till that point and had a degree of financial independence. I was in a job as an investment analyst where I enjoyed the work but was frustrated that I had zero say in the investment decisions (something that became more frustrating the more success I had with my own investments). I was deeply inspired by what I saw in Omaha, particularly how happy Buffett was allocating capital to the best of his (considerable) ability and not worrying a jot about what other people thought. It was what I aspired to do for myself. After I got back from Omaha that May, my mind was made up.

I did not speak to any potential clients before leaving my job and starting RV Capital. I felt that the decision was my responsibility, and it would have been unfair to offload it to my clients. However, once my decision was official, my first call was to Herrn Rentrop, whom I had previously met through an investment we shared. As is typical for him, he invited me to Bonn. Shortly thereafter, he became my first client. The mandate was not huge, but in conjunction with my savings and modest outgoings (I was a professional couch surfer long before Airbnb was a thing), it was enough to keep the lights on almost indefinitely. As an entrepreneur, I was off to the races. This was Herr Rentrop’s first decisive intervention in my life.

Two years later, Herr Rentrop made a second decisive intervention. When I started RV Capital, it had always been my dream to run my own fund. However, it was a distant prospect. I faced the chicken-and-egg dilemma that many aspiring independent fund managers will be only too familiar with – without a track record, it is impossible to attract capital, but without capital, it is impossible to start building a track record. By this time, I had been managing part of his family’s capital in a separate account. I asked him whether I could use that capital to seed a fund. He agreed, and the Business Owner Fund opened its doors to business on 30 September 2008. I was now not just an entrepreneur but an independent fund manager.

As a side note, the 30th of September was a few days after the collapse of Lehman Brothers and close to the height of the Great Financial Crisis. I can imagine that a lot of financial promises made in a rosier economic climate were not kept in those troubled times. Herr Rentrop’s cheque cleared.

These are perhaps the two most decisive interventions that Herr Rentrop has made on my behalf, but he has helped in many other ways, too.

Don’t tell Warren, but the first time I travelled to Omaha was to attend a German-speaking value investing conference that Herr Rentrop organizes around the Berkshire weekend. The Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting was a peripheral benefit. Attending that event introduced me to German and international value investing networks from which all my investing contacts and friendships have originated. It also exposed me to the Berkshire Hathaway meeting, which was a key factor in my decision to go it alone. Had I not received that invitation, things likely would have turned out differently.

Herr Rentrop also taught me the importance of judging the character of the managers I invest in and, most importantly, only investing in companies run by managers with the highest integrity. When I first visited him in Bonn to discuss some of my investing ideas, he asked me if I had ever done a background check on the major shareholder of one of the investments I proposed. I had not. He obviously had but did not spare me from doing Google searches together. I sank a little deeper into my chair as each search showed up a new example of corporate malfeasance. I was devastated that I had made such a mess of my first meeting with my first and, at the time, only client. Fortunately, his aim was only to educate, not castigate. It was an important lesson, and I learned it viscerally.

As a side note, I do not think that most investors viscerally get how important it is to invest in managers with talent and integrity. It is so obvious that it is easy to overlook. Not everyone is lucky enough to almost lose their sole client over the topic.

There are many more examples of how Herr Rentrop has helped me and many others. But I will stop here and reiterate my thanks. Herr Rentrop will be in Engelberg this coming January, so if you are an investor in the Business Owner Fund or have benefited from the fund’s existence in other ways, please be sure to stop him and pass on your thanks, too.

A First Investment in the Oil and Gas Sector

In late 2023 and early 2024, we purchased a stake in International Petroleum Corp (“IPCO”) (STO:IPCO).

IPCO is an oil and gas company with production in Canada, France, and Malaysia. It is based in Vancouver, Canada, and has a dual stock market listing in Canada and Sweden. Its market value is around US$1.5 billion.

IPCO produces approximately 46’000 to 48’000 barrels of oil equivalent per day (“boepd”). For context, the world consumes around 100 million boepd, so it is a minnow in an enormous market. Approximately 85% of its production is in Canada. It is currently developing the Blackrod project there, which, when completed, will bring a further 30K boepd online. Its 2P reserves, i.e. reserves that are proven and probable, are 468 million boe, equivalent to 27 years of production.

IPCO began life in April 2017 when it was spun out of Lundin Energy onto the First North Nasdaq. Lundin Energy wanted to focus on its Norwegian assets and thought its international assets would benefit from the additional focus of a separate listing. IPCO's roots go further back than 2017 though. In the 1980s, Adolf Lundin, started a company that was also called International Petroleum. That company disappeared as part of a series of transactions that ultimately led to the formation of Lundin Energy. As a nod to the past, the name was revived for the spin-off. IPCO’s Bertam oil field in Malaysia also came out of the original International Petroleum, providing a further link to the past.

IPCO’s track record since its inception has been spectacular. It started out with little production or reserves, but had the advantage of owning some producing assets and a debt-free balance sheet. Today, its reserves have increased by 16x, and its share price has quadrupled. Despite the massive increase in reserves, IPCO has minimal net debt and, at the current rate of share buybacks, will soon have reduced the share count to the same level as when it was listed.

IPCO achieved such prodigious growth through smart M&A and improving the assets it owns. It has made five acquisitions since its inception, but two were particularly significant. In 2017, it bought Suffield in a debt and cash transaction, and in 2018, it bought BlackPearl Resources in a stock-based transaction. Both companies operate in Canada and were bought for a song when Canadian oil and gas were deeply out of favour. In the case of Suffield, Cenovus (the seller) was effectively a forced seller as it had bought heavy oil assets from Conoco and had to offload its conventional oil assets to finance the deal. IPCO was the only credible buyer with cash on hand and cherry-picked the best assets.

IPCO fits well into the paradigm of an industry roll-up, but this does not give it sufficient credit for its operational expertise. In the earlier years, it grew primarily through M&A, but more recently, it has pivoted to organic growth and opted to develop the enormous Blackrod resource that came along with the BlackPearl acquisition. The company feels equally comfortable growing intrinsic value by investing organically, doing M&A, or simply buying back its own stock.

IPCO's major shareholder with a 34% stake is the Lundin Family, a Swedish family with extensive holdings in the mining, oil and gas, and renewable energy sectors. It is a fascinating family that I have enjoyed learning about as part of the research into IPCO. The family business was started over 50 years ago by Adolf Lundin. The book "No Guts No Glory" documents his many adventures and his highly enjoyable.

As it relates to the energy sector, the family's most significant investment was Lundin Petroleum (later renamed Lundin Energy) developed by the second generation. Lundin Petroleum was listed in 2001 when it raised $70 million at a share price of SEK 3. It never raised capital again and was sold to Aker BP in 2022 for SEK 400 per share, leaving the original shareholders with a 175x return. The family continues to hold a 14% stake in Aker BP. Today, the family's holdings are managed by four brothers in the third generation. I met three of the four brothers. The fourth missed lunch as he was closing the US$ 3 billion acquisition of Filo for Lundin Mining with BHP, so I guess he gets a pass.

IPCO is run by Will Lundin, one of the four brothers. At 31 years old, Will is a young CEO. However, he does not lack experience. He told me he grew up listening to discussions about the commodities business around the family dinner table. After studying Mineral Resource Engineering in Canada, he worked as a field engineer at BlackPearl Resources (yes, the one IPCO later bought) before taking up a position at International Petroleum in 2018. In 2020, he became the Company’s COO, and earlier this year, he became the CEO after the retirement of his predecessor, Mike Nicholson.

I have gotten to know Will over the last couple of years and am incredibly impressed. He is humble and hardworking, which is even more impressive given his privileged background. I spoke with his former boss at BlackPearl, who told me that Will kept his head down and got things done. What has particularly impressed me is the people he surrounds himself with. I have gotten to know several of IPCO’s senior executives and board members, as well as senior executives of the family’s other investee companies. They are all cut from the same cloth. They are the kind of people who cannot stand the BS of big companies, love what they do, draw small salaries, and have a big upside when projects work out, as they invariably do. It is the kind of place where people can get rich together and generally do not leave. Corporate types would not last five minutes there.

Competitive Advantage

Commodity markets do not lend themselves to wide moats. By definition, the price of a commodity is defined by the market rather than by differentiation between producers. This leaves cost as the main way to compete. The lower down the cost curve a company is, the greater its profits at any given oil price and the lower its breakeven point.

IPCO has a mixture of conventional assets that are lower down the cost curve and heavy oil assets that are higher up the cost curve. Increasingly, heavy oil will dominate the mix, given the large investment in Blackrod. They are less moaty than older, conventional wells. However, the world developed the easiest-to-reach oil first, so any new development will, almost by definition, either be higher up the cost curve or in a geographically unstable region. Importantly, though, it has a lower cost than North American shale, which is the marginal capacity in the industry.

Where IPCO clearly has a moat is in its culture. It is rational and entrepreneurial, as its stellar track record demonstrates. It should also endure over time. Good people are attracted to the company and stay. This is a big advantage in an industry dominated by corporate behemoths and not known for its rationality across boom and bust cycles.

An Attractive Valuation

The biggest challenge when valuing a company such as IPCO is the oil price. It will have a huge impact on revenues but in the future is neither known nor knowable. I have no ambition to be able to predict it. My observation as an outsider is that the price has swung wildly in the past and will likely do so in the future. Oil consumption should decline, in particular, as the electrification of transportation gathers pace. So, too, should supply. There is a natural decline rate in existing fields; there is increasing societal resistance to new supply; and our need for many oil derivatives such as fertiliser, petrochemicals, and aviation fuel are not going away any time soon. There will likely be no shortage of material for market commentators to justify the inevitable boom and bust cycles. The volatility should provide a fertile hunting ground for a rational capital allocator like IPCO.

What can be known is the company’s net asset value (“NAV”) and how much cash it is likely to produce under different oil price scenarios. At its capital markets day in February, IPCO outlined its NAV calculation for 2029 under two different scenarios. In the first scenarion, it assumes the Brent oil price is $75, and it can repurchase its stock at SEK 115. In the second scenario, it assumes an oil price of $95 and a stock price of SEK 215. This results in NAVs of SEK 757 and SEK 1’228. Both imply substantial upside over a five-year holding period. Opportunistic M&A represents an additional source of upside.

Oil companies are notoriously overly optimistic in their NAV calculations, but I am confident that IPCO’s assumptions are realistic. The Lundin family has no intentions to sell, and IPCO is enthusiastic about repurchasing its own stock. With overly optimistic projections, it would do itself no favours.

What is also knowable is how much cash the company will produce in the coming years under different oil price scenarios. From 2024 to 2028, under oil price assumptions of $75 and $90, IPCO expects to generate $900 m and $1’800 m of free cash flow, respectively, or 65% and 131% of its current market capitalisation. Even including the large investment in Blackrod, it will return most of its market cap in cash in the coming years, giving us a cheap or free option on what it earns after 2028.

An Oil Company, Really?

Many of you were surprised to see IPCO in the quarterly factsheet. Perhaps it is because we have not invested in the oil and gas sector before. Perhaps it is because the sector is notoriously cyclical and capital-intensive. Or perhaps it is because it falls foul of ESG criteria.

I have always been positively disposed to the sector. Oil is a product we cannot do without and likely won’t be able to do without for some time to come. It is a hedge against geopolitical disruptions, as when there’s a crisis somewhere, the oil price tends to go up whilst everything else goes down. And valuations have seemed cheap for a while. What held me back was the predominance of large corporations with professional managers in the sector. This is not the sweet spot for the Business Owner fund to invest. What gets me excited are companies run by passionate owners.

As an aside, it is not unusual for me to invest in “new” sectors or countries, so I hope newer investors are not disorientated. On day one, the fund was made up mostly of German small caps. It raised eyebrows when I bought a big tech company in 2012 (Google (NASDAQ:GOOGL)), a Chinese company also in 2012 (Baidu (NASDAQ:BIDU)), a big pharma company in 2013 (Novo Nordisk (NYSE:NVO)) and a loss-making tech company more recently (Carvana (NYSE:CVNA)). I enjoy learning about new companies and believe it is essential for the long-term success of the fund.

The way I approach an investment in an oil and gas company is the way I approach any investment. I look for a growing moat, an attractive valuation, and rational and engaged managers, ideally, who are owners. Valuations in the energy sector have been attractive for a while, and moats are easy enough to ascertain as they are primarily a function of where a company sits on the cost curve and its culture. What held me back in the case of the oil and gas sector was the final criterion – good long-term owners and managers. In this respect, I am very excited to have found IPCO.

Oil From a Sustainability Perspective

I can imagine that, given the role of oil and gas in causing climate change, the investment raised eyebrows among some of you. A section of this letter is dedicated to the broader topic of Environment, Sustainability, and Governance, or “ESG” for short.

With regards to the “E” in “ESG”, I, too, am concerned about climate change and the negative impact of burning hydrocarbons on the environment. However, I respectfully disagree that the correct response is to allocate capital away from the oil and gas sector. The world requires investment in sustainable technologies and, until the time arrives when the energy transition is complete, investment in the oil and gas sector. If we do not continue to produce oil, the result will be rampant inflation in the rich world and economic collapse in the developing world. It is difficult to think of a more ethical investment than one upon which the survival of humanity depends in the short to medium term, whereby I acknowledge it is also a threat to humanity in the long term. To get to the long term, though, you must first negotiate the short term.

A China Basket

In the first half of the year, I added one additional Chinese company to the portfolio - NetEase (NASDAQ:NTES), a video gaming company. Since the end of the period, I added three more - Yum China (NYSE:YUMC) (the operator of KFC and Pizza Hut in China), H World (NASDAQ:HTHT) (the second-largest Hotel company in China) and Didi (OTCMKTS:DIDIY) (the dominant rideshare platform in China). This takes the total number of investments in China to six. I do not rule out buying further investments, but I will cap the overall China exposure.

The valuations in China are the most astonishing I have seen in my investment career, including during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008/09. Take the companies we own. They are blue chips with dominant competitive positions in their respective industries. They are highly profitable. They have oodles of net cash. They are growing at the top and bottom line despite the struggling Chinese economy. Despite these favourable characteristics, they trade at P/Es ranging from mid-single digits to low double digits, and five of the six are aggressively returning cash to shareholders. The most aggressive is Yum China, which is returning US$1.5 billion p.a. on a market cap of $13 billion at our cost, equivalent to a 12% shareholder return. These valuations are not idiosyncratic to the companies we invested in but are ubiquitous.

As an aside, Chinese companies have undergone a sea change in recent years in terms of returning capital to shareholders and their overall competitiveness. I remember when the consensus was that Chinese companies would never return capital and would never amount to more than low cost manufacturers. When it comes to reporting on China in the West, it seems that the good news travels slowly. Many Chinese companies have started aggressive capital return programs. Lufax, a financial services company, even paid a dividend earlier this year that was greater than its market capitalization. The continuous discussion about trade tariffs and import bans is, in essence, an acknowledgement in the West that Chinese companies are increasingly hard to compete with across all sectors.

My approach to investing in China is more diversified than has historically been the case. Each investment is around 3% of the portfolio except for Prosus (a proxy for Tencent), which is around 10%. You may view this as a departure from the highly concentrated approach to investing that has characterised the Business Owner Fund to date. However, concentration has never been an end in itself; it is a function of great opportunities being rare. When opportunities are abundant, it makes little sense to concentrate. Why take the risk of betting on the one stock that does not work? Furthermore, if the China portfolio is viewed as a sub-portfolio, it is still highly concentrated with just six stocks.

I am conscious that investing in China is far from risk-free. As Spiderman’s Uncle Ben might have said on the topic of investing:

"With great opportunity comes great risk."

However, I believe we are getting paid to take the risk. Without wishing to step on Uncle Ben’s toes, the bigger the opportunity, the lower the risk. Risk can, by definition, never be greater than 100% in an unleveraged portfolio such as ours, so the greater the upside, the more favourable the overall risk-return calculation. Moreover, the risks of investing in China are very much top of everyone’s mind. In my experience, the risks that no one has on their radar tend to be the ones that catch you out.

This is necessarily an abbreviated summary of some of our newer China investments, as there are other topics I wanted to cover in this letter. I will likely dive deeper into the investment hypotheses of the individual investments in my 2024 letter.

ESG Investing

Having purchased a stake in an oil and gas company, I think it is a good time to describe my thinking on ESG investing. For the uninitiated, “ESG” stands for “Environmental, Social, and Governance” and is a framework for evaluating a company's ethical and sustainable practices. Whilst it was once a niche area of investing, it is now firmly mainstream. Investors in funds want to have a positive impact on the environment and society. Many ESG funds have been launched to meet the customer demand.

Companies or sectors that are thought to be bad for the environment or society or to have poor governance score low on ESG criteria. Oil, mining, fast fashion, fast food, alcohol, and defence are all examples of sectors that have low ESG scores and are generally excluded from ESG funds. Given that we own an oil company, a legitimate question is whether I am indifferent or even hostile to ESG.

To answer that question, I would draw a distinction between ESG in theory and ESG in practice.

I Am Pro-ESG in Theory

I care deeply about the issues that ESG investing raises. I am concerned about climate change. I am conscious that sometimes women and minorities do not have equal access to opportunities because they cannot access established networks as effortlessly as people like I can. I firmly believe that good governance is a prerequisite for good outcomes for shareholders and, more broadly, Society.

This is not just lip service. When I started the Business Owner Fund, governance was at the forefront of my thinking. The name of the fund reflects my strong conviction that companies with rational and engaged owners generally have the best governance. At our Annual Gathering in Engelberg, I open my network up to as broad a community as possible. And Sustainability has informed my investment decisions. My concept of a sustainable investment is one that creates a win-win between customers, suppliers, employees, and Society at large. In my letters, I have generally described why the companies we are invested in create a win-win with all stakeholders.

My Reservations are with ESG in Practice

Being pro-ESG as an idea is not the same as being pro-ESG in practice. I have many objections to ESG investing, but I will limit myself to six.

Ignorance of trade-offs

My biggest objection to ESG guidelines, particularly when it comes to the environment, is the failure to account for trade-offs. This is most obvious in the case of oil and gas (yes, they cause CO2 emissions, but no, we cannot survive without them). Trade-offs are everywhere when you look for them. Mining companies are extractive, and yet electrification is dependent on copper, lithium, and many other mined materials. Guns are used to murder innocent people but might be the ultimate sustainable investment, as Western Europeans are rediscovering, if you have a bellicose neighbour.

There are many more examples of trade-offs I could give. In fact, I struggle to think of any sector - even the most unpalatable - where there are no trade-offs whatsoever. Take tobacco. I despise smoking and would be heartbroken if any of my children took up the habit. But if the activity is not illegal and people are properly informed about the risks, should they not have access to a “safe” product if they choose to use it?

As an aside, I consider trade-offs to be one of the most overlooked and powerful lenses through which to view the world. If you find yourself violently disagreeing on any topic with an otherwise reasonable person, take a step back and ask yourself if there are trade-offs at play. It will likely lead to an improved understanding of the world and (I hope) improved relationships.

The bottom line is that most activities might seem to be undesirable when viewed purely from the perspective of their downsides. An intelligent approach weighs the upsides against the downsides. ESG guidelines generally miss this nuance.

Misunderstanding Business’ Impact

ESG funds tend to underestimate the role of business in solving the world’s most intractable problems and, as a corollary, overestimate their own. The ESG industry is not the motor that will drive to better environmental, social and governance outcomes. Companies are. It is markets and the companies that operate within them that create innovations that solve environmental problems, that create employment and that reward owners when governance works.

I am not a market absolutist. Markets sometimes fail. Where this is the case, there is a role for thoughtful intervention. However, my concern is that, in particular, the younger generation is left with the impression that all businesspeople are bad and any good outcomes are thanks to intervention. The opposite is the case. When a large business fails or rips off its customers, it makes headlines. What this tells you is not that all businesses are bad but that most are good. The bad companies are rare enough to be newsworthy, not the good ones.

Independence is the Wrong North Star for Governance

Regarding governance, i.e. how companies are overseen, I believe the overall direction is completely wrong. The core idea of modern governance reform is that directors should be independent. In practice, this means that they do not have a significant ownership stake in the company they are overseeing. I frequently hear from my fellow investors that their request for board representation is declined as they are told by the CEO or existing board members that their shareholding represents a potential conflict of interest.

This is absurd. For all its good intentions, socialism’s fatal flaw was the separation of ownership from responsibility, and yet, this is the one aspect that the ESG industry seems to consider worth preserving. The idea of independent directors is effectively socialism without the idealism.

In any case, no one is ever truly disinterested. When directors do not own a stake in a company, they do not cease to have interests. Their interest is just more likely to be their own. Their interest is generally maximising their earnings and minimising their risk. They achieve the former by endearing themselves to the CEO to maximise their stay on the board and the latter by adopting a “cover-my-ass” mentality. I spoke recently with the CEO of one of Germany’s largest companies. He stepped down as it was increasingly impossible to get anything done given the timidity of the Board of Directors. The board refused to make even the most minor decisions without first receiving a comfort letter from lawyers.

Having interested board members is essential for the long-term success of companies. Last year, our portfolio holding Carvana restructured its debt at favourable terms for all stakeholders. I heard privately that it could do this as the bondholders held no leverage over the Board of Directors. The way these things typically go is that the bondholders approach the Board, point out its fiduciary duty to ensure the company remains a going concern, and threaten to sue the board members individually if the company goes bankrupt. The directors nearly always cave to whatever bondholders demand. Thanks to the Garcias' large shareholding, bondholders had no such luck at Carvana.

Boards need to be interested, not disinterested.

The Arbitrariness of ESG Criteria

ESG criteria strike me as highly arbitrary. What many people consider to be an ethical investment tends to better reflect their own lifestyle choices than an objective measure of morality. People who feel insecure in foreign cultures or are simply afraid of flying take a critical view of the CO2 emissions from air travel; People who hate shopping take a dim view of the waste from fast-fashion retailers. And people that do not use social media blame it for all of society’s ills. The reality is that in the developed world, most people’s basic needs for food and shelter are more than adequately covered. What makes life rich and worth living are the indulgences. For each of us, these are different.

Take me as an example. I hate shopping. I do not smoke. I don’t play video games. And I avoid fast food. Want to ban the fashion, tobacco, gaming and fast food industries? Be my guest. However, lest you thought that Mahatma Gandhi has been reborn as a fund manager in Switzerland (unlikely, I admit), I have a CO2 balance from air travel that would make Taylor Swift blush (OK, maybe not quite). If I want to keep my vices, maybe I will have to let you keep yours.

Bureaucracy

One of the biggest consequences of the boom in the ESG industry is an explosion in bureaucracy. It has spawned rating agencies that are hungry for data and ESG funds that are hungry for the highest ratings. What this has led to is a proliferation in data collection, much of which is irrelevant. In a best-case scenario, it is a cost and a distraction. In a worst-case scenario, it prevents things from getting done altogether. When I was in East Africa a few weeks ago, I heard directly from entrepreneurs that many essential projects are slowed down by the documentation requirements that come along with EU money (in roadbuilding, for example) and, in some cases, are blocked altogether (in cement, and oil and gas projects, for example). This is a sub-optimal outcome for all economies, but especially those that need development the most.

Effectiveness

I question how effective ESG funds are at catalysing the change they seek, which is perhaps for the best, given how wrongheaded some of their goals are. The main mechanism ESG funds use to catalyse change is to buy the companies that score highly on ESG criteria and sell those that do not. I fail to see what this is supposed to achieve. Ben Graham points out that in the short term, the market is a voting machine, and in the long term, it is a weighing machine. These “votes” may influence the share price in the short term, but ultimately, the value of any investment is the cash it produces over its lifetime. Buying or selling shares won't change that. The net impact is likely to be a transfer of wealth from ESG funds to non-ESG funds.

The ESG industry would no doubt argue that an ESG framework helps to identify winning investments and avoid losing ones. But if this is the case, is it not reasonable to assume that investors will adopt it whatever? A market intervention is only necessary if the market delivers sub-optimal outcomes when left to its own devices. If I thought a company was going to go out of business because it was making profits at the expense of employees, customers or the environment, I would not buy it. I do not need to be an ESG fund to make the right decision.

One possible exception is if a company needs to raise capital to finance a new project. A buyer boycott could drive up the cost of capital and make the project unviable. However, it is relatively rare that companies need to raise capital. This is especially the case in highly profitable industries, which is often the case where competitors are discouraged from entering them due to ESG criteria. Do not hold your breath on the next capital increase at Philip Morris (NYSE:PM).

If you want to effect change, surely there are better ways to achieve it than selling good investments and buying bad ones based on ESG criteria rather than a rational appraisal of the investment's prospects. It is a recipe for underperformance.

The existing ESG framework is a blueprint for bureaucracy, wrong incentives, and underperformance. We will not be applying to be an ESG fund any time soon. To repeat, this is not because I do not care about the environment, our companies' impact on society, or governance. I care deeply about all three.

What Would I Do Differently?

Scrap the Entire Governance framework

I would scrap the entire governance framework as it exists today. It is irreparable as it is based upon a flawed assumption that ownership and governance need to be separated. Owners should be actively encouraged to get involved in the governance of the companies in which they allocate their investors’ capital, not dissuaded from doing so. This is not an argument that only the mega-rich should be allowed on boards. The size of the investment is unimportant. It just needs to be a big part of the individual’s net worth.

Reduce Regulation

This one will be counterintuitive to many people, but I would reduce regulation. Regulation is sometimes necessary, and it sometimes works. However, more often than not, it doesn’t. Regulation is often ineffective as companies find a way around it, and its sole impact is raising the overall cost of doing business. It has unintended consequences. For example, the biggest impact of privacy regulation in the EU has been to entrench the incumbents who can afford to comply with it. And Regulations costs are not explicit. Many regulations prevent companies from getting started, or once started, from growing to their full potential. In the most extreme cases, they prevent entire markets from coming into existence.

Make New Laws

Where there is ambiguity about a sector's desirability, lawmakers should be the ultimate adjudicators. There is a debate to be had on whether gambling, tobacco, drugs, and other activities should be made legal, illegal, or restricted. The correct forum for this in a democracy is our parliaments. The self-appointed leaders of rating agencies and mega funds should not get to decide what activities are encouraged and which ones are shadow-banned. Of course, governments, like markets, are fallible, and when they fail, there is a case for individuals to exercise their own agency. However, this agency should be used infrequently and surgically, not across the board, as a matter of policy.

Make Trade-Offs Explicit

Trade-offs should be made more explicit. You think oil and gas are bad for the environment? Fine. But what are the impacts of banning new production? You want more regulation of big tech companies? Fine. But what are the impacts on competition? You want to ban targeted advertising? Fine. But how are small businesses supposed to find customers? And to the extent they cannot, what are the millions of people who work for them supposed to do?

With any proposal, the trade-offs should be made explicit. People should not get away with proposing an idea and only listing the benefits or censoring it and only listing the costs.

Finance Moonshots

My final wish would be for more capital to be focused on moonshots. I find it frustrating that much of the capital that flows into the ESG industry tends to go into funds that simply buy the market, excluding a handful of companies with low ESG scores. I do not see what good this does. What can really move the needle, in particular with regard to the environment, are technological breakthroughs. Venture capital does a good job of financing companies that promise a return over the life of their funds. This leaves a gap in the market for ideas that may take decades to come to fruition, if at all, or have an impossibly low probability of working, making them borderline philanthropic. To the extent that people are willing to give up some return in order to leave the world a better place, this strikes me as a more productive route to go down than an ESG fund that is handicapped from investing where returns are potentially the highest but is otherwise no different from any other fund.

Annual Gathering in Engelberg

Oil, China, ESG…my sense is that there will be no shortage of topics to discuss at our Annual Gathering in Engelberg next year. The meeting will take place on the weekend of the 11th and 12th of January 2025. Andreas and I look forward to welcoming you. Registration will open at 3:00 pm CET on Friday, 4 October. If you are an investor in the fund, you have a guaranteed spot. If not, you are welcome to come, but we recommend setting an alarm for next Friday as the spots tend to be snapped up quickly.

Until then, happy investing, and stay healthy!

Rob