Abstract: With high growth rates during the past two decades and the largest trade surplus with the United States, China is the primary target of the U.S. trade war efforts. Tariffs are the first shot in bilateral tensions that are multilateralizing and injuring global economic integration, coupled with ever more intense technology competition. The evolving global sce- narios of U.S.-China trade and technology conflicts are the outcome of an ever more anxious America forsaking its multilateral cooperative stances for primacy doctrines. In the worst case, these conflicts may escalate into a “decoupling” of both economies and cause lasting global recession and new geopolitical confrontation. This gloomy scenario has become viable with the exceptional use of executive power by the post-9/11 U.S. administrations. The Trump administration, in particular, is predicated on “imperial presidency” that relies on an emergency status quo, new cam- paign finance, and “big money,” which poses significant risks not only to U.S.-China relations, but also to American democracy and existing inter- national order.

Q1 hedge fund letters, conference, scoops etc

Rising U.S.-China Tensions and Waning Globalization

Today, globalization led by the United States and other advanced econo- mies is winding down, while China-fueled globalization, which is driven by emerging economies, has grown to be a complement. As “America First” policies surge in Washington, the attractiveness of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the BRICS1 New Development Bank (NDB) has significantly increased in developing economies. Nevertheless, both the Obama and Trump administrations, in contrast to their major trade part- ners and other Group of Seven (G7) members, have largely limited the U.S. from participation. Similarly, Washington has kept its distance from the China-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) despite its openness toward U.S. participation ——— President Trump even labeled the Initiative as “insulting.”2 The U.S. goal may be to contain China’s economic rise or divide Asia, or both, as evidenced by hardened sentiments3 and efforts to pressure China on its trade, investment and technological policies, while taking many “divide and rule” measures in the Asia-Pacific. On the economic front, for example, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo gave a speech on

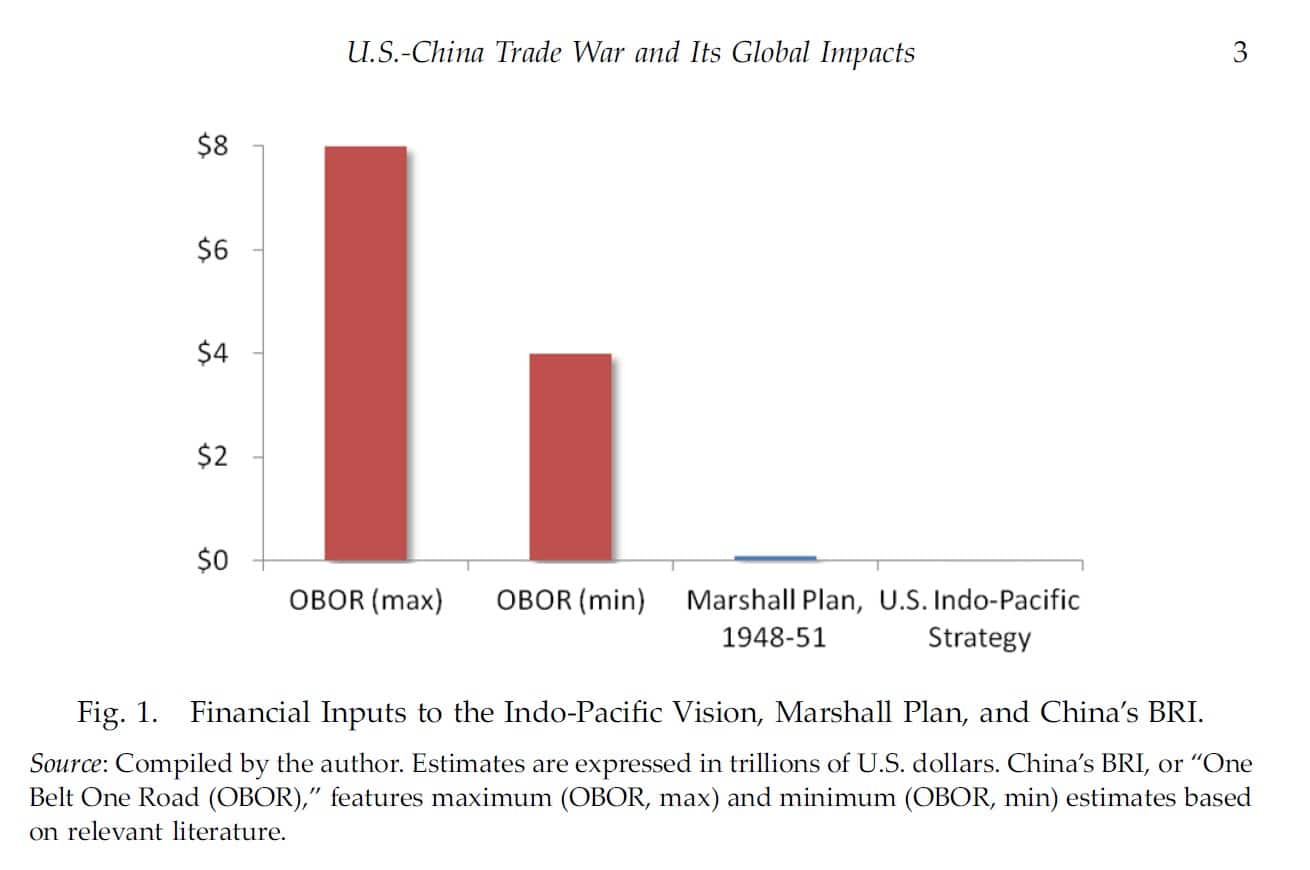

“America’s Indo-Pacific Economic Vision” on July 30, 2018, in which he announced $113 million in new U.S. initiatives to “support foundational areas of the future” in the regional economy, energy, and infrastructure.4 But the scale of the “Indo-Pacific Economic Vision” pales in comparison with the BRI, which involves far greater cumulative investments estimated at around $4 trillion to $8 trillion,5 dwarfing even the Marshall Plan from 70 years ago (as Pompeo alluded to), whose cumulative aid may have totaled $12 billion, or about $180 billion in today’s dollar value (Figure 1).

Indeed, what Asia needs is not new geopolitical divisions, but a sustainable, long-term plan for accelerated economic integration and development, indicated by the overwhelming consensus among Asian countries on working to reach a free trade agreement of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) that includes the United States.6 However, that is not what the Trump administration wants.

U.S.-China Trade Tensions

The United States and China are the world’s leading powers in terms of the size of their economies, defense budgets, and global greenhouse gas emissions. Both nations are permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. In 2017, they were each other’s largest trading partners. This bilateral relationship is perceived by many to be the most conse- quential in the world. The global importance of the U.S. and Chinese economies, as measured by their nominal gross domestic product (GDP), can be illustrated in two ways that will also illuminate the challenges of the ongoing power transition: one involves the rise of the Chinese economy relative to the U.S. GDP; the other focuses on the concomitant shifts in globalization.

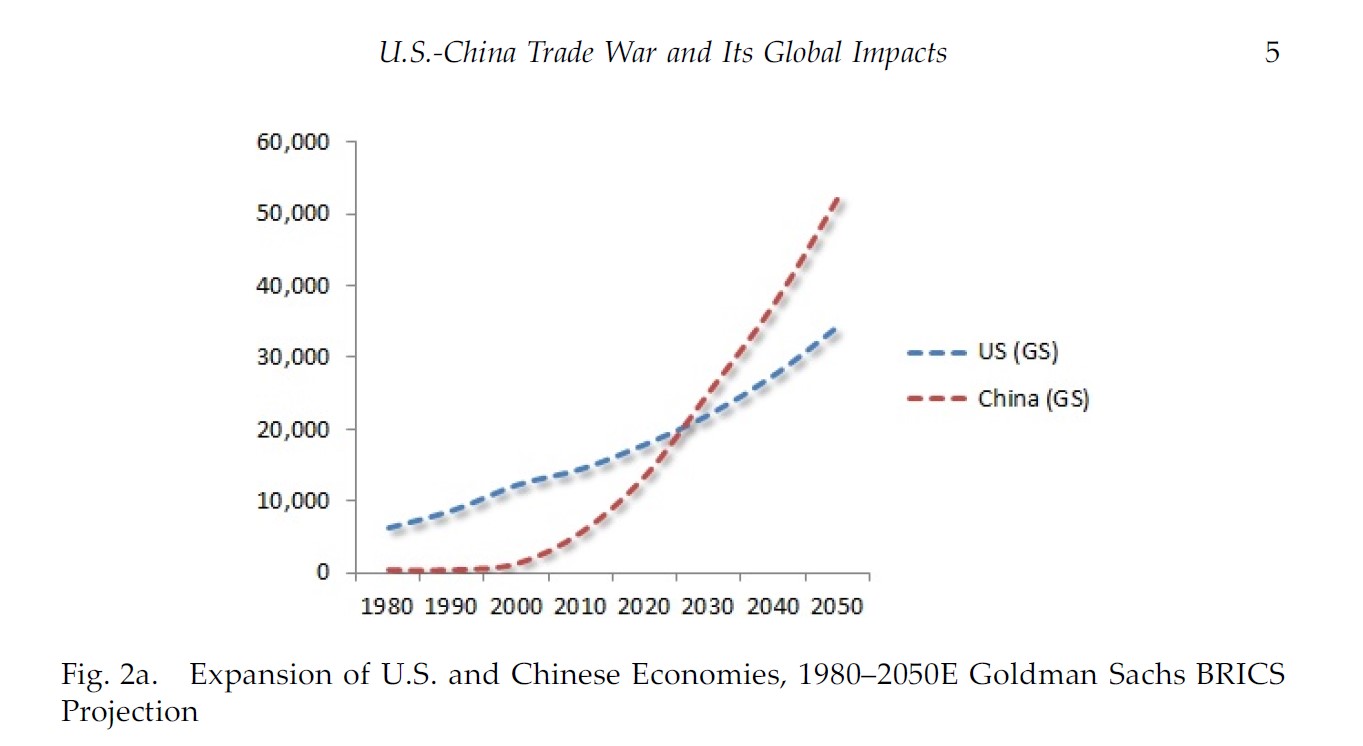

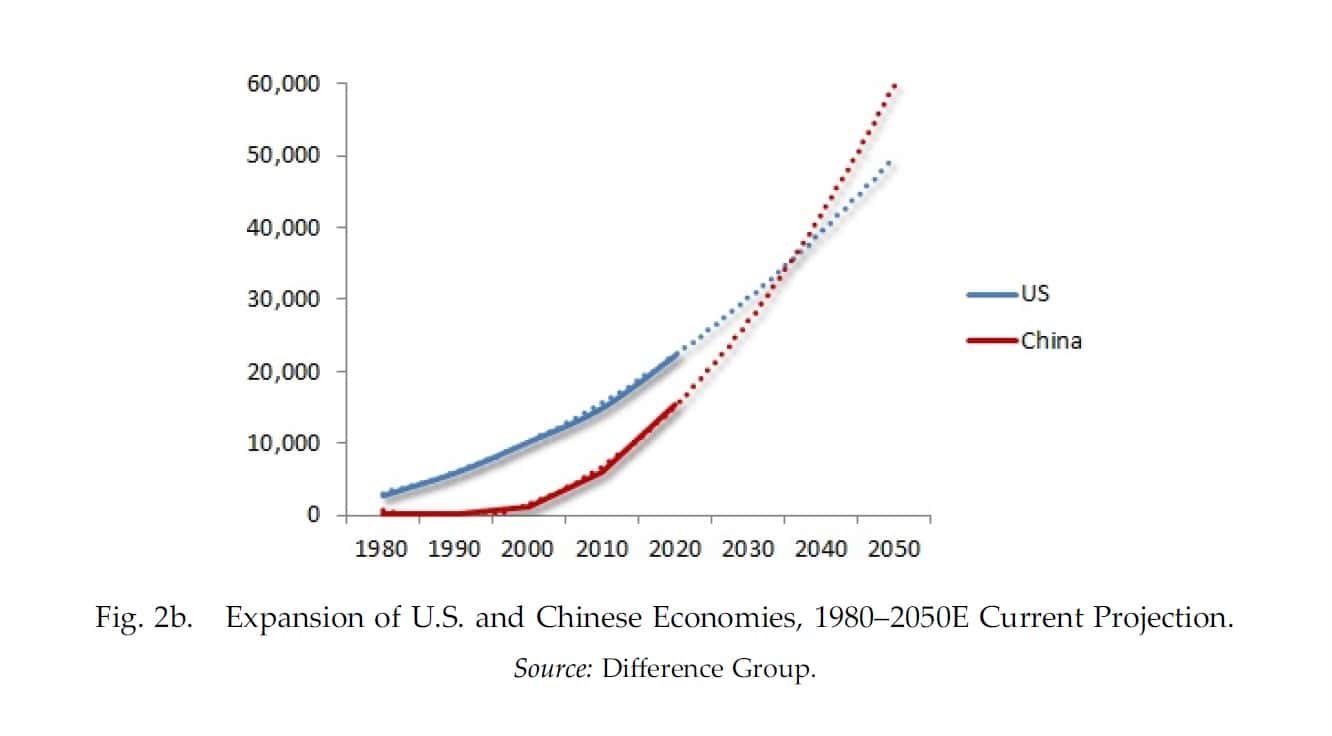

In 2000, China’s economy was barely a tenth of the U.S. GDP. But after China became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, its export-led growth soared in the course of the 2000s, when its share of the U.S. economy more than tripled from 12 percent in 2000 to over 40 percent in 2010. The original Goldman Sachs estimate was that China would sur- pass the United States in the late 2020s (Figure 2a); and that remains the case under Xi Jinping’s leadership, assuming current secular trend lines prevail (Figure 2b).

Yet there are two major caveats to the Goldman Sachs projections: the first involves international trade prospects amid rising U.S. protectionism; the second has to do with the impact of these trade actions on the conse- quent global prospects. After a year of threats, the Trump administration initiated a “tariff war” against China in March 2018. The measures became effective in early July 2018. What began with “national security reviews” on steel and aluminum soon extended to intellectual property rights and technology. Even worse, bilateral frictions with China are spreading to U.S. trade conflicts with other North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) members, Europe, East Asia and practically the rest of the world.

If the Trump administration continues moving away from the post-World War II trading regime, these bilateral frictions will broaden and multilateralize. And if a full-scale trade war cannot be avoided, then the nascent tariff wars have po- tential to spread across industry sectors and geographic regions. In fact, since the first half of 2018, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) growth projections have already been revised down for Europe, Japan, the United Kingdom, Brazil and India, among other major economies. The most im- portant is how well the Chinese economy will do amid growing trade tensions with the United States. China accounted for almost 50 percent of global growth and continues to constitute some 30 percent of global pro- spects today. In positive scenarios, such economic spillovers support global growth. In negative scenarios, such spillovers would penalize those growth prospects and the collateral damage would likely be the worst in emerging and developing economies.

Challenge to Global Economic Integration

Recent globalization peaked between China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 and the global financial crisis in 2008. After the crisis, China and large emerging economies fueled the international economy, which was thus spared from a global depression. But as Group of Twenty (G20) cooperation has dimmed, so have global growth prospects and the future of global economic integration.7

Before the global financial crisis, world investment soared to almost $2 trillion. A decade later, global flows of foreign direct investment have fallen by almost 20 percent below the pre-crisis peak.8 In 2017, world merchandise trade recorded its strongest growth in six years. But due to rising trade tensions and increased economic uncertainty, the WTO warned that global trade growth is losing momentum and that downside risks have grown in the global economy.9 Following the financial crisis, there has been a dramatic fall in global finance as well. Meanwhile, global debt has continued to swell but has remained stable relative to world GDP (at about 169 percent) since 2014.10

There is nothing inevitable about global economic integration. It may be useful to recall that, about a decade ago in July 2008, then-WTO Director-General Pascal Lamy declared that there was “qualified public support for globalization,” and that “[g]lobalization will not come to halt.”11 Only weeks later, trade depression spread across the world. Ten years later, Trump’s tariff wars began to hurt a trade recovery that had taken a decade to materialize. In adverse conditions, they could even fuel serious global recession in the years to come.

See the full article below.