Markets & Macro

Markets & Macro

News

Stay on top of the latest hedge fund news with Hedge Fund Alpha! The investment world is always in motion, so it’s never been more important for investors to stay informed on what hedge funds are doing. We bring you timely, accurate reporting on top hedge funds like ValueAct, Citadel, Greenlight Capital, Third Point, Pabrai Investment Funds and more. Dive into the diverse perspectives presented by Hedge Fund Alpha and go behind the headlines here. Hedge Fund Alpha is your go-to source of hedge fund news. From breaking news to developing stories, we have our fingers on the pulse of the hedge fund community and investment universe. Check out all the top headlines here with Hedge Fund Alpha.

Markets & Macro

Markets & Macro

Markets & Macro

Markets & Macro

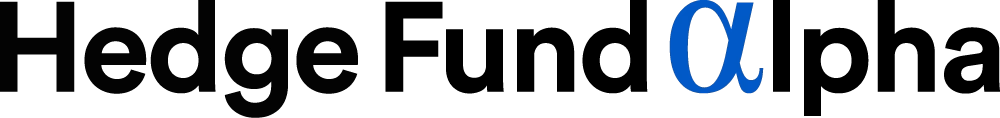

Policy Shifts And Private Assets: The Changing 401(K) Landscape

Value Briefs

Value Briefs

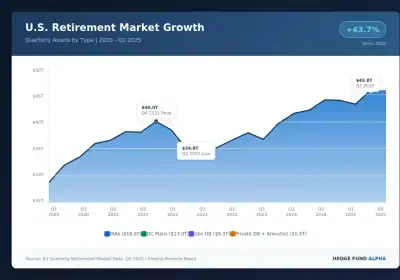

Investing Wisdom From The Oracle Of Omaha: Key Takeaways – LPL

Hedge Fund News

Hedge Fund News

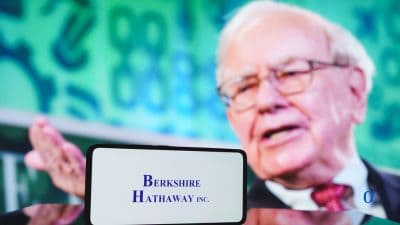

2025 Hedge Fund Winners Confirmed As Systematic Funds Gain Early 2026 Traction

Hedge Fund News

Hedge Fund News

The Volatility Paradox: How New Hedge Fund Managers Can Turn Early Success into Long-Term Success [In-Depth Weekend Read]

Markets & Macro

Markets & Macro

Global Securities Lending Revenue Hits $15B In 2025; These Were The Most Popular Stocks

Press Releases

Press Releases

RPD Fund Management Caps Strong 2025: Fortress Delivers 34 of 35 Positive Months; Opportunity Fund Gains ~40%

Hedge Fund News

Hedge Fund News

2026 Hedge Fund Trends: Mega-Funds, AI, Quants, And Talent Wars To Dominate Headlines

Year-End Hedge Fund Scorecard: Equitile M3 Returns to the Forefront

Hedge Fund NewsMarkets & Macro

Hedge Fund NewsMarkets & Macro

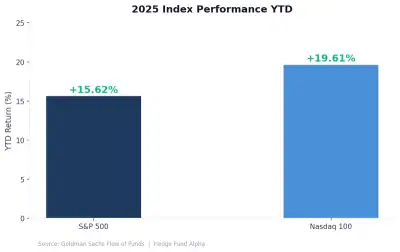

Low Vol, High Concentration, and $11 Trillion on the Sidelines: Goldman’s Fund Flow Review

Hedge Funds On Strongest Streak In A Decade Posting Eight Consecutive Months of Gains

Hedge Fund News

Hedge Fund News

Top Performing Hedge Funds In 2025: Penta Japan Value In Lead Up 75% YTD, And High Flying Crypto Fund In Last

Hedge Fund News

Hedge Fund News

Grizzly Research: Ceres Power’s Revenue Is Tiny; Story Is Hype

Press Releases

Press Releases

Axyon AI launches game-changing Agentic AI platform for thematic investing: Axyon Foresight

Press Releases

Press Releases

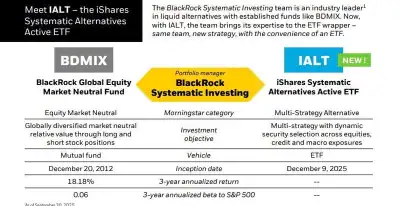

BlackRock Expands Liquid Alts with New Multi-Strategy Active ETF IALT

Press Releases

Press Releases

Strong growth sees private credit market reach $3.5 trillion

Value Briefs

Value Briefs

Berkshire Hathaway Announces Leadership Appointments; Todd Combs To Leave & Join JPMorgan

Hedge Fund News

Hedge Fund News

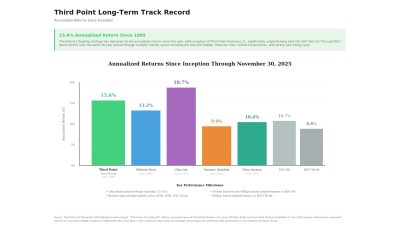

Third Point Dumps Primo Brands Amid “Overestimate”; Sells Out Of Meta & Apollo, Reduces Amazon Stake [Exclusive]

Press Releases

Press Releases

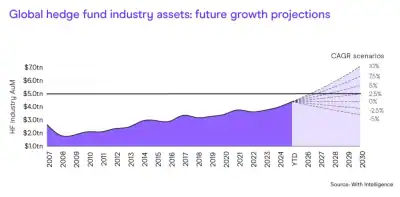

Hedge Fund AUM Could $7 Trillion By 2030; UAE Fund Launches Soar; Smaller Multi-Strat Catch Up: HFR

Press Releases

Press Releases